How to take care of unruly archives

A conversation with Lisa Darms, editor and archivist of The Riot Grrrl Collection

Lucie Ortmann (Essen)

During the 1990s, members of the US American feminist movement Riot Grrrl articulated their message not only in punk rock, but particularly in multimedia fanzines and flyers, which they hand-lettered, drew, then copied and stapled and distributed themselves. These publications came out irregularly and they often lack dates or numbers. The book publication The Riot Grrrl Collection (The Feminist Press 2013), edited by Lisa Darms, presents a plethora of printed matter previously only available in local and limited editions to a new, broader audience. Alongside the reproduction of entire zines, excerpts and flyers, the book also includes samples of letters, hand-written lyrics and drawings, all presented in roughly chronological order. The size of the printed matter and other pieces of writing, sketches and drawings is adapted to the pages of the book – this makes the size of the individual documents more uniform, which helps legibility, but also subdues differences at first sight.

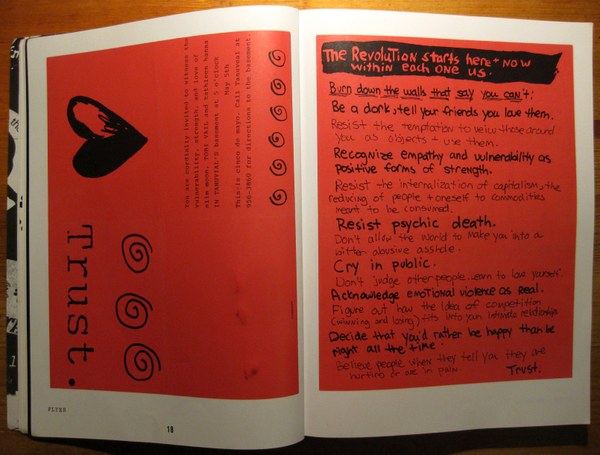

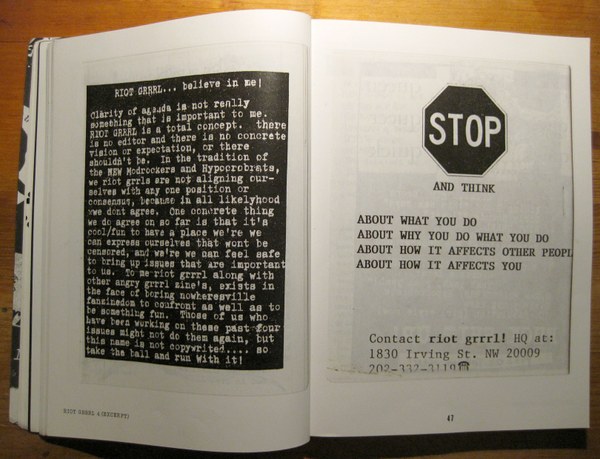

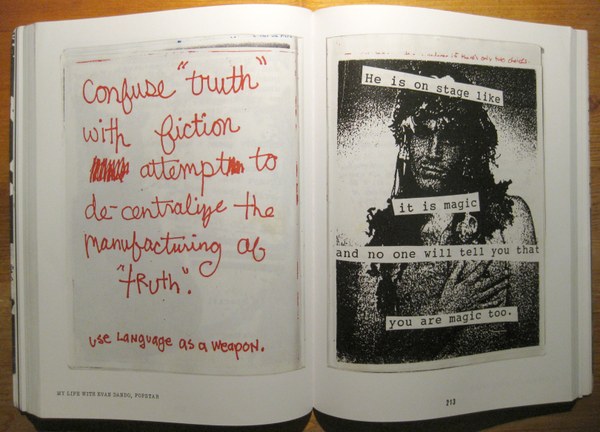

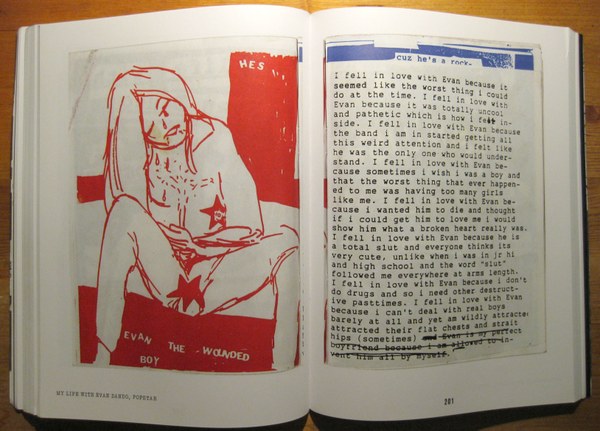

Fig. 1-3, Flyer [The Revolution starts Here and Now…]. Kathleen Hanna, 1990. The Kathleen Hanna Papers. [Darms 2013: 18-19]. By courtesy of Kathleen Hanna; Zine: Riot Grrrl no. 4. Molly Neuman, Allison Wolfe, and others, circa 1992. The Kathleen Hanna Papers. [Darms 2013: 46-47]. By courtesy of Molly Neumann, Allison Wolfe; Zine: My Life with Evan Dando, Popstar. Kathleen Hanna, 1993. The Kathleen Hanna Papers. [Darms 2013: 212-213]. By courtesy of Kathleen Hanna.[1]

The book decidedly focusses on the Riot Grrrl movement collection founded in 2009 as part of the Fales Library & Special Collections at New York University, as the entire published material is part of this collection. The Fales Library & Special Collections has been led by Marvin Taylor since 1993 and specializes in the archiving of artistic and activist movements, trans-disciplinary projects as well as collaborative and collective work processes. In 1994, Taylor founded the Downtown Collection as a documentation site for the artistic and activist scene in Downtown New York, SoHo and the Lower East Side from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. The collection has grown to approximately 200 archives, ranging from Judson Memorial Church to the A.I.R. or Guerilla Girls collectives, to the personal documents of punk icon and author Richard Hell, performance artist Martha Wilson or artist and author David Wojnarowicz.

Between 2009 and 2016, Lisa Darms was the senior archivist at Fales Special Collections, where they had to learn “how to preserve, describe and make accessible” non-traditional archive material. [cf. Keenan 2013: 63] She soon suggested to Taylor to start a collection on the Riot Grrrl movement. [2] Even though it was not rooted in New York, but rather developed around universities in Olympia, Washington and Washington D.C., the Riot Grrrl movement shares similarities in form and content to the Fales Special Collections, particularly the Downtown Collection. Its affiliation to the institution resolutely puts the Riot Grrrl movement in the contexts of experimental art and activism.

The Collection overall includes zines, letters, notebooks, clippings, source material for zines, journals, draft lyrics, cassette tapes, videotapes, vinyl recordings, performance props, clothing, a skateboard and more. Each archive is very different, depending on the person who created it, and ranges in size from one small box, to 12 boxes. [Darms 2018]

The personal archives can be described as “unruly” or “wild”, they are structurally ordered as grown or growing, developing in an organically complex way.[3] They refuse any traditional separation into processes and products /“works” and continuously re-negotiate the boundaries between public and private. Lisa Darms explains:

Ethnomusicologist Elizabeth K. Keenan elaborates further:

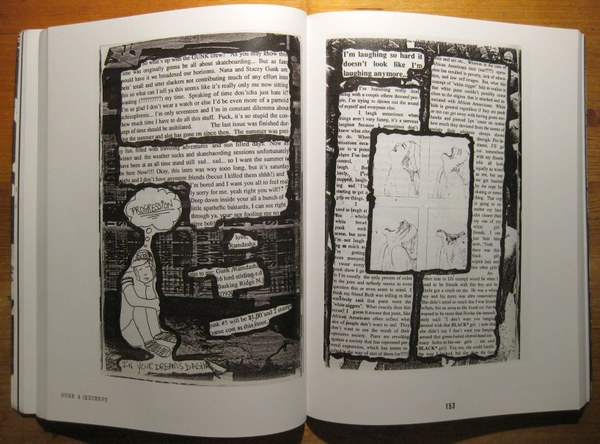

Fig. 4-5, Zine: Gunk no. 4. Ramdasha Bikceem, circa 1993. The Ramdasha Bikceem Riot Grrrl Collection. [Darms 2013: 152-153]. By courtesy of Ramdasha Bikceem; Zine: My Life with Evan Dando, Popstar. Kathleen Hanna, 1993. The Kathleen Hanna Papers. [Darms 2013: 200-201]. By courtesy of Kathleen Hanna.

In 2018 I discussed the specific qualities of the Riot Grrrl Collection with Lisa Darms in an email interview. We examined how she deals with the collection’s complexities and contradictions as an archivist and historian, but also as the editor of the book.

Lucie Ortmann: Marvin Taylor talks about trying to question the structures of the library within the library itself. How do you avoid the standardization of archives and libraries at Fales and especially with the The Riot Grrrl Collection? Moreover, can you give us an impression of how registration works?

Lisa Darms: The Riot Grrrl Collection is made up of over 20 individual archives. Each archive was created and/or collected by an individual or entity (the “creator”, in professional parlance). The significance of this is that each archive’s meaning is found not only in the individual items within it, but also in its aggregate identity as formed by its creator: how it was collected, how it was arranged, what was excluded, and the relationships between the documents and objects. Then, each individual archive is catalogued using the standards outlined in Describing Archive: A Content Standard.[4]

Ortmann: Who uses the Collection and for what purposes?

Darms: The Collection is used by all kinds of scholars, from queer theorists to historians of graphic art; teenage zinesters; artists; college students; and many more.

Ortmann: As part of the research project Media and constitutive systems: Archiving performance-based art, I am especially interested in open and fluid accesses to collections, in how an archive can become appealing for alternative use, re-interpretation or further development by others, such as artists. Is this type of practice promoted and/or explored in the Riot Grrrl Collection? Can you give examples?

Darms: I’m not sure what Fales is currently doing to facilitate non-traditional access. At least when I was there, we were very understaffed and under-resourced—The Riot Grrrl Collection represented about 5% of my work responsibilities, and it was difficult to find any time for creating alternative modes of use. That said, I aimed to promote the Collection and create a welcoming Reading Room. Artists and other non-scholars were always using the Collection in non-traditional ways, which was part of our approach at Fales overall. I also put a lot of energy into teaching with the materials.

Ortmann: The Riot Grrrls created their own, self-determined popular culture and media. Now their self- and handmade publications are reproduced in a book and their personal papers are part of an official collection. Does that mean this vivid and intense movement has become institutionalized and musealized? How do you as the editor and archivist keep the stubborn, unmanageable qualities and anti-establishment strategies productive?

Darms: In terms of the actual Collection, I was more concerned with this in the beginning than I am in retrospect. I think the importance of preserving these radical and complex materials, in an increasingly conservative and reductive time, so that they can have a public life into the future outweighs what is mostly a symbolic “institutionalization”. By being in an archive, the materials are available for use and reuse and inspiration and rejection, far more so than they would be if they were still in the boxes under beds and in storage units they were in before the formation of the Collection. That said, I think an ideal scenario is one in which there are many Riot Grrrl Collections—some in moneyed institutions like NYU, others in community-run spaces, others perhaps primarily online like the queer zine project QZAP. As for the book, I think it actually works against musealization by bringing the documents into circulation, without academic or aesthetic interpretation or theorization.

Ortmann: What were the premises of selection for the book? What audience did you have in mind?

Lisa Darms: The book was a way to give access to the Collection on a much broader level than what is possible for an archival collection. The book is meant to be read, it is overtly not an aesthetic object (e.g. a “coffee table book”). Although the book is for anyone who wants access to the original documents, without interpretation, I did have in mind a teenage reader who would be inspired by the achievements and mistakes of the early movement to create their own forms of revolution.

The premises of selection for the book were to represent the movement accurately, using only the materials that were in the Collection, and showing a broad swathe of viewpoints within a specific timeframe. I wanted to represent the complexity and divisiveness and vulnerability of the actual movement. I wanted to represent the Collection in its breadth as well, but because I was unable or unwilling to reproduce most personal materials, like letters and diaries, the book has much more print material (zines and flyers) proportionally than the collection overall does. I asked permission to reproduce zine excerpts. In a few cases, permission was not granted, and those items were not reproduced.[5]

Ortmann: In your introduction to the book, you express the wish that it functions as a manual: a set of instructions for remaking the world [Darms 2013: 12]. For me this is connected to the activist and educational verve of the movement that wanted to widely inspire, enlighten and empower. How much did the practices of the riot grrrls blur the boundaries between producer and recipient? What role did authorship play overall?

Darms: You’ll see that many of the early zines, like Bikini Kill and Girl Germs, are collectively authored. Then there are the friendship books, in which a handmade zine would be added to page-by-page, through the mail, one person at a time. In addition, some women/girls used pseudonyms. As well, Xerox technology enabled not only the “original” author to create and distribute their zine, but anyone could continue to copy and share it, although with some image degradation. However, since that degradation of the image inherent to Xerox recopying was an aesthetic, it was not necessarily a loss.

Ortmann: Did the practices of the Riot Grrrl movement challenge the concepts of private and public?

Darms: I believe the tension between private and public is innate to 1990s Riot Grrrl. The movement came out of punk subcultures of the late 1980s, at a time when DIY media, music and activism were (and, before the internet, could be) sequestered. The goal to create alternative economies had driven many of these communities, and so the idea of a “separate” culture resulted in a private or anti-public culture. At the same time, many riot grrrls wanted to enact a revolution for all girls everywhere, not just those who were part of these small punk enclaves. These two impulses were hard to reconcile. For many riot grrrls who had been misrepresented by mainstream media, there was a suspicion and rejection of “public” culture. This inwardness in some cases just perpetuated mini-monocultures and a kind of elitism.

Personal archives in general also contain this tension between private and public, containing intimate documents that were never meant for anyone else, but are now part of larger historical discourses that demand public access and reproduction. This is further complicated by the contemporary expectation of “access” as a democratic right, compounded by the ease of access to information on the internet.

Ortmann: With today’s online world and social media in mind—like blogging for instance—it is very interesting to take a closer look at discussions on the public sphere in context of the riot grrrls. The zines were originally distributed by spreading them personally, girl-to-girl or on demand by mail. Some producers/authors emphasized safety and intimacy and only addressed their output to a specific scene. Does this have something to do with the intimate themes that were also shared in the zines, such as personal accounts of violence?

Darms: I assume here you might mean first-person stories of sexual abuse and rape? Yes, a limited and specific readership (or, if shared in a meeting or at an all-girls show, “audience”) was assumed. The possibilities of mass online distribution and the “flattening” of potential audiences could not be predicted, which is why I did not reproduce these personal stories in the book. At the same time, the expression of these stories in a semi-public “safe” space was part of a process of healing for some, and for destigmatization, so that some kind of audience was required. However, that audience had a context. Of course, the “safe spaces” of second and third wave feminism have been rightly critiqued for being safe only for some—assuming a shared commonality that did not exist. Nevertheless, the ability to select an audience or create a community that feels supportive can be crucial to the processes of self-exposure that bring violence to light.

Ortmann: The Riot Grrrl Collection to a great extent includes material from the process of production, ranging from preliminary stages of production to material that was not directly included, to actual “works”. Do the activities of the riot grrrls challenge the concept of a “whole” product, a piece of work?

Darms: I believe that all archives present this challenge. The innate characteristic of an archive (especially those of performers, artists, writers and activists) is process. This creates a fascinating entrée into the vulnerable moments of the creative process; into half-formed ideas and out-and-out failures; and, in this Collection, to younger, in-process selves, since the archive donors were in their teens or very early 20s when they created these collections.

Ortmann: The focus on the moment and the simultaneous intensive activity of collecting is striking. What is the relationship between the cursory, unique production for the present moment, a now and its extensive documentation—especially in regard to the producers themselves? What motivated them to collect? Was it historical awareness or rather a sense of emotional connection?

Darms: Riot Grrrl demanded Revolution Grrrl Style NOW. At least in my own experiences at the time, the belief in and desire for actual revolution was real. For me, this urgency precluded any thought of a possible historicized future. However, unlike me, I think there were many girls and women who were well aware of the erasure of the work of feminist foremothers, and therefore made an effort to document their activism. I also think that the patterns of fandom within punk created a collecting culture. Even if you lacked a sense of feminist history, it might already be second nature for you to collect flyers and records and fanzines. In addition, the anticapitalist impulse to create alternative economies (and don’t forget that early Riot Grrrl was explicitly anticapitalist), which created DIY photographers and writers and record labels (and eventually librarians), also created networks of self-documentation.

Ortmann: Thus, the protagonists/producers were fans themselves. It seems that somehow passion became strategy.

Darms: I think everyone who created fanzines was both a “fan of” and had the potential to be or become the object of fandom, similar to the way a girl might see a band, pick up a guitar, and then become a musician, creating new fanbases and new systems of activist networks.

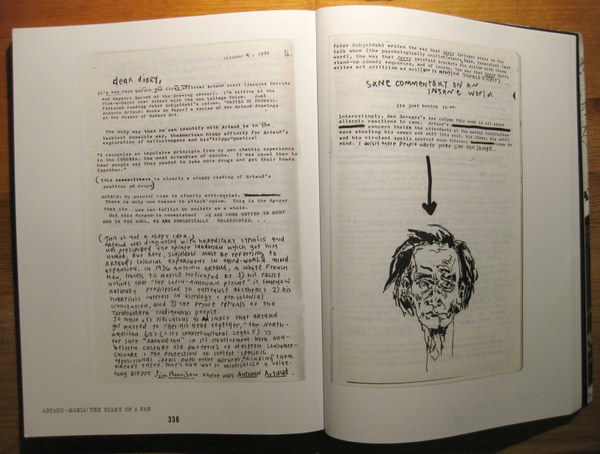

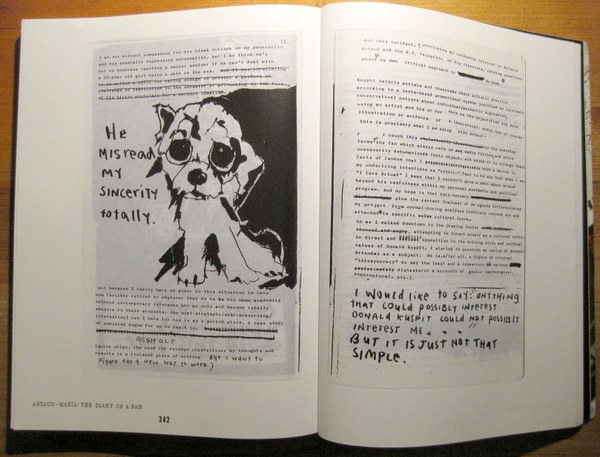

Fig. 6-7, Zine: Artaud-Mania: The Diary of a Fan. Johanna Fateman, January 1997. The Johanna Fateman Riot Grrrl Collection. [Darms 2013: 336-337, 342-343]. By courtesy of Johanna Fateman.

How closely linked fan behaviour and archiving are, was explored in the 2016 exhibition at Deutsches Filmmuseum Frankfurt Zusammen sammeln. Wie wir uns an Filme erinnern (Collecting together. How we remember films). This exhibition predominantly presented personal collector items and memorabilia supplemented with objects from the collection and archives of Deutsches Filminstitut. The exhibition illuminated “…in what manifold ways films are retained in our memories, how private individuals and institutional archives collect, and how blurred the boundaries between them can be.” [original German quote: Deutsches Filmmuseum Frankfurt 2016]. The Archiv für Popmusikkulturen at the University of Freiburg’s Zentrum für Populäre Kultur und Musik added Reinhold Karpp’s Rolling Stones collection in 2017, which includes 15,000 recordings, memorabilia and fan merchandise. These two examples not only illustrate the permeable boundaries between individual and institutional collecting, but also how documentations of everyday and popular culture are usually collected by private individuals. This particularly applies to artistic or activist sub- and counter-cultures as they are documented in the Fales Special Collections. In other institutions, however, they purposely leave little to no traces. With its ties to fandom and affective, affirmative association to particular scenes, nostalgia becomes an often-discussed aspect in the context of Riot Grrrls and the Downtown Collection. Marvin Taylor addresses this in his interview:

And in a conversation between Lisa Darms, Johanna Fateman and Kathleen Hanna held during the book presentation, the latter explains:

Translation: Margarethe Clausen