Artistic Processes of Archiving in Contemporary Dance

Tokyo / Singapore: Archive Box Project (2013-2016)

Lucie Ortmann (Hannover / Dresden)

Curating potentiality and latent power (rather than products)

In October 2015 curator and film director Ong Keng Sen presented his engaging concept of ‘curating nothing’, a term coined in reference to Jean-Luc Nancy, at a symposium held as part of the project SHOW ME THE WORLD – Curatorial Practice in the Performing Arts in Munich. Ong divides his work into two categories of curating, ‘informal curating’ and ‘formal curating’. Examples for the former are his Flying Circus Project and Archive Box Project, while the latter includes his work as artistic director for the Singapore International Festival of Arts. In both cases, ‘curating nothing’ is a key term in his work as it means to activate processes as a political act, instead of producing or launching products that are prone to political exploitation. He has sparked debate on issues like community, creative commons, and sharing forums. His aim is to empower communities to create the future [The Saison Foundation 2015: 8].[1]

The Flying Circus Project is a multidisciplinary artistic research project, started in 1996, which brings together artists (first from the region of Asia, since 2007 from all over the world). It follows the self-proclaimed goal of not producing any pre-conceived result. In Munich, Ong Keng Sen drew parallels to related subversive practices such as wasting money, or deconstructing value. He considers these practices curatorial resistance against the colonization of the arts by productivity. One example of this strategy was to use part of the festival budget allotted to a specific production point for something completely different, such as digitalizing a threatened film archive in Myanmar. The idea of curating nothing is closely tied to ‘curating potentiality and latent power (rather than products)’.

In 2013 Ong Keng Sen, together with The Saison Foundation[2] in Tokyo, Japan, called to life a project on archiving dance, which subsequently became the Archive Box Project. In the following years it was realized in three phases oscillating between mediation, collaborative research and artistic practice. Ong Keng Sen links his project to the idea of how to encourage processes:

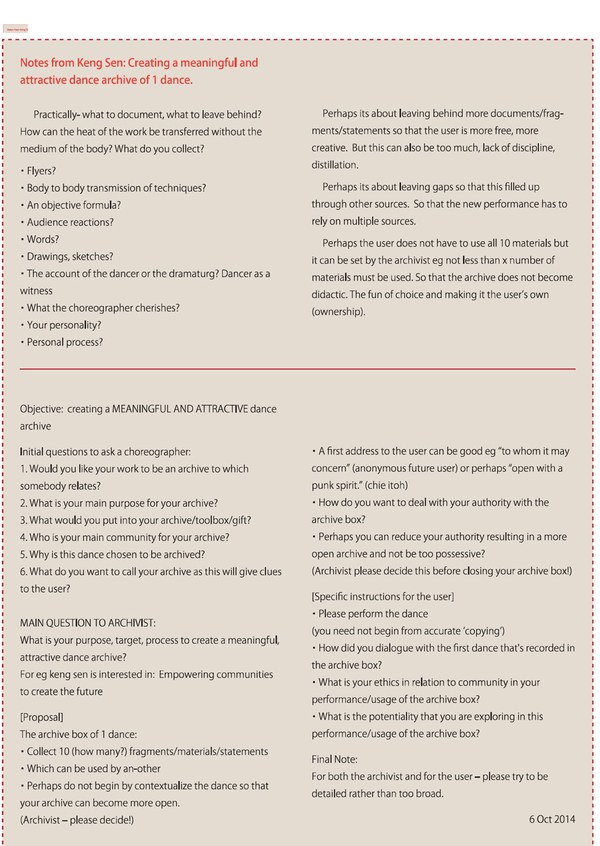

Fig. 1: Notes from Ong Keng Sen, October 6, 2014

[The Saison Foundation 2015: 8]

Participants and the development of Archive Box Project

The first to participate in Archive Box Project were the facilitators who planned the process, (re-)adapted the project to new developments, and curated and organized events. The team included Ong Keng Sen, dramaturg and dance scholar Nanako Nakajima as well as the two dramaturgs Daisuke Muto (Tokyo phase) and Margie Medlin (Singapore phase). Together with the Saison Foundation, the team of facilitators selected the archivists, eight Japanese dancers, to join the process: Chie Ito, Ikuyo Kuroda, Ryohei Kondo (who only participated in the first workshop), Tsuyoshi Shirai, Yukio Suzuki, Natsuko Tezuka, Zan Yamashita, and Mikuni Yanaihara. Nanako Nakajima elaborated on selection process in an interview:

The archivists participated in a series of lectures and workshops held between April and December 2014, exploring and discussing the possibilities and methodologies of (dance) archives. The next step was to create an archive of one of their own works. Then they performed the archive material of another archivist before a selected audience. Ong Keng Sen suggested approaching the material “as if playing a game” [see The Saison Foundation 2015: 60]. Here the archivists also took on the role of users (phase 1)[3].

The idea of an ‘archive box’ as a tool was developed within the collaborative process, as Ong explains:

Users were a second group of participants in the project, namely in the phase that took place within the framework of the Singapore International Festival of Arts in February and March 2015. Again, this phase consisted of a brief tutorial followed by a workshop, in which artists performed one of the previously archived works (phase 2). Ong Keng Sen invited the following seven dance artists from South Asia and Southeast Asia to participate: Preethi Athreya, Padmini Chettur, Chankethya Chey, Margie Medlin, Rani Nair, Venuri Perera and Mandeep Raikhy.

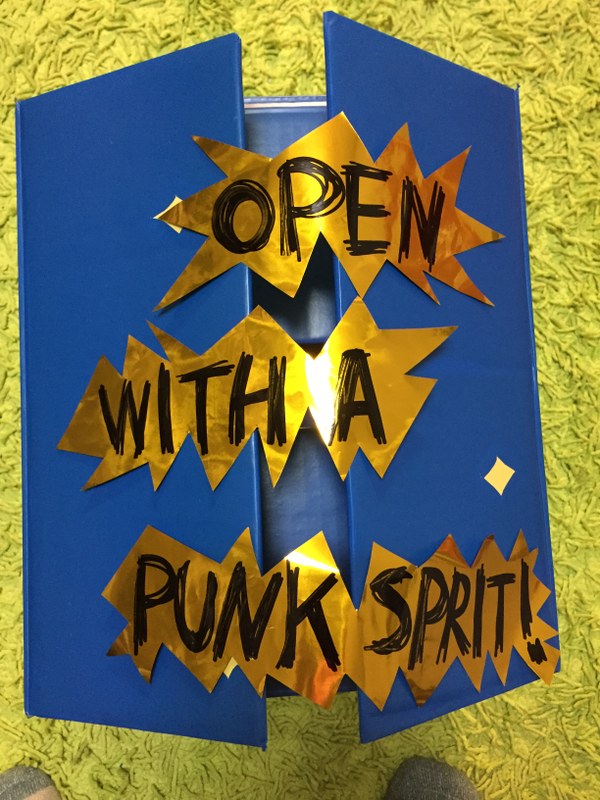

Originally, the project was supposed to end in the event Dance Marathon: OPEN WITH A PUNK SPIRIT! Archive Boxes at the festival, where users performed the works and archivists presented their ‘boxes', thus bringing together all 14 artists.[4] Following Nanako Nakajima's initiative, however, a further series of performance-dialogue sessions between archivists and users, an exhibition and a symposium – titled Dance Archive Boxes@TPAM 2016 – were held as part of the Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama in April 2016. This third phase also included new dance artists such as Oohisui Hanayagi, a young, emerging dancer and student of Toshinami Hanayagi, who is considered Important Cultural Property in traditional dance in Japan. Hanayagi chose to perform Chie Ito's archive box.

PHASE 1

Kontemporari dansu (contemporary dance) in Japan

How did the decision come about to archive the contemporary dance scene in Japan? To mediate its works, to make them accessible to a broader audience? Nanako Nakajima explains that in Asia, Japan was the first to have an independent, innovative contemporary dance scene [Nakajima 2016b]. She also detects a political context in Ong Keng Sen addressing aspects of community and access to contemporary dance in Asia. In the Saison Foundation report, she notes:

Nakajima also explains that there is no archive culture in Japan comparable to western traditions. In fact, traditional performing arts are ruled by strict hierarchies, often including secret forms of passing on knowledge taking place within family-like, closed structures.

Dancers are connected in a global network; they contribute to contemporary discourses and shape developments, by addressing themes such as the practice of reenactments, or by following the debate on how to deal with the legacies of dancers and choreographers like Pina Bausch or Kazuo Ohno. Daisuke Muto, dance scholar and university lecturer, points out another important aspect of archiving contemporary dance in Japan:

The boxes: The archive as a toolkit

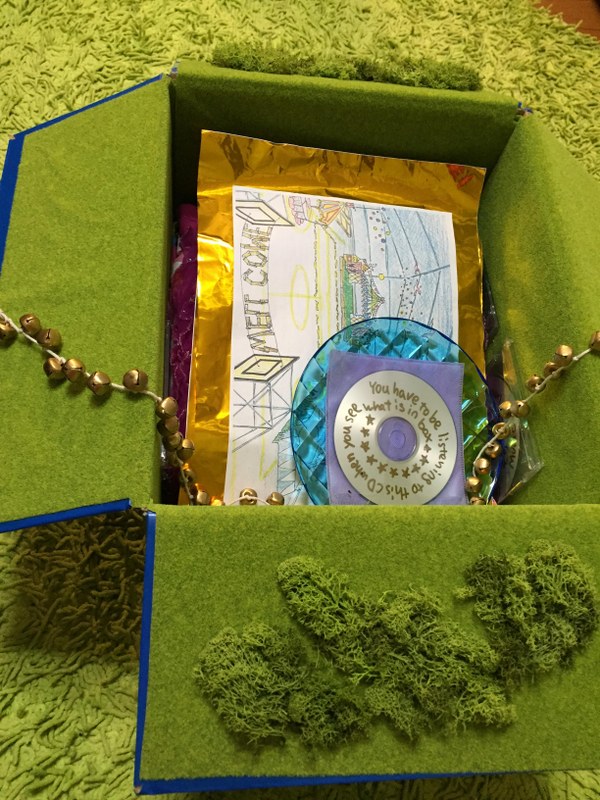

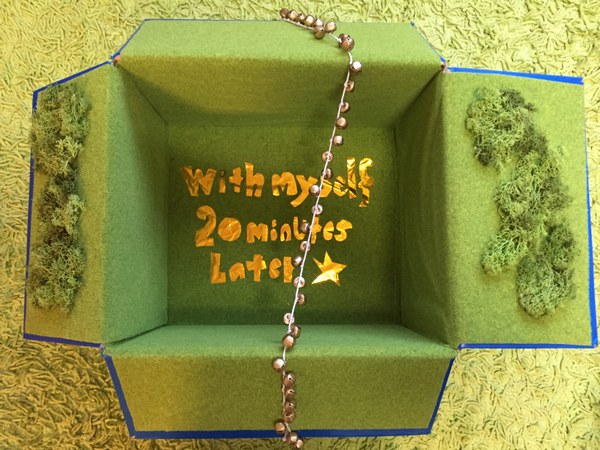

The seven participating Japanese artists, who each created an archive of their own works, developed individual, often contrary concepts of the archiving process. Thus their resulting archive boxes vary greatly.[5] Chie Ito, for example, was the only one to make an actual box, which she wrapped in gold, and in a later version in blue paper and adorned with trinkets and small bells. She also attached a note encouraging the user to “Open with a punk spirit!”.

Fig. 2-4: Chie Ito's gold and blue versions of her box. Fig. 2: Courtesy of the artist,

© The Saison Foundation, Fig. 3, 4 © Chie Ito

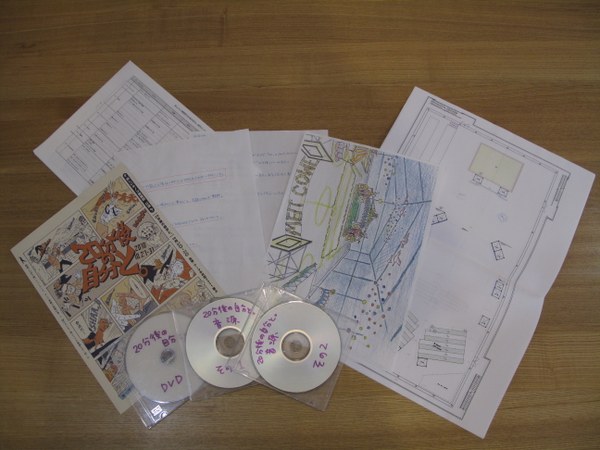

In her box, she archived several costumes and props, an instruction manual, a stage plan, a drawing, video documentation (DVD), a soundtrack (2 CDs) and flyers. Ito notes:

Fig. 5-7: Pictures of the material inside Chie Ito's box. Fig. 5 © Chie Ito,

Fig. 6, 7: Courtesy of the artist, © The Saison Foundation

In the report, Mikuni Yanaihara reflects the aspect of time and how the box may be used:

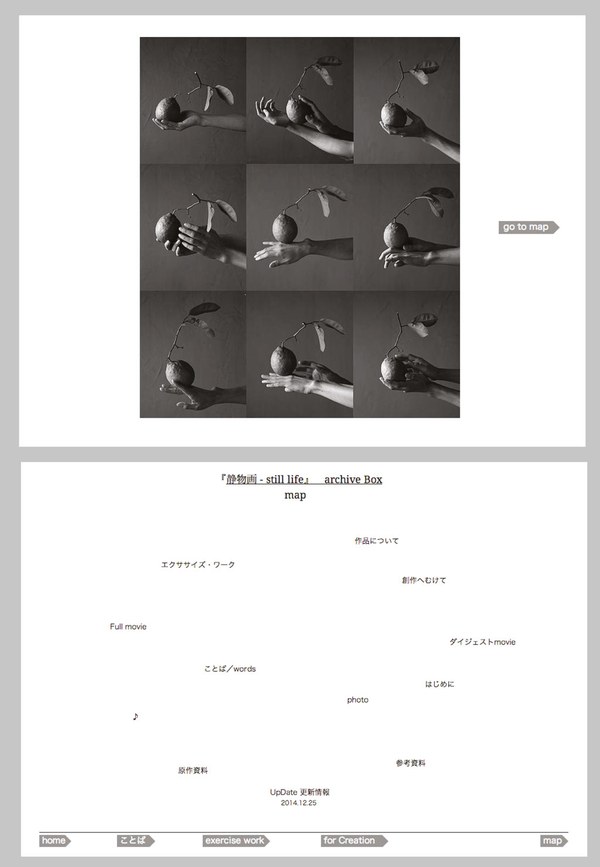

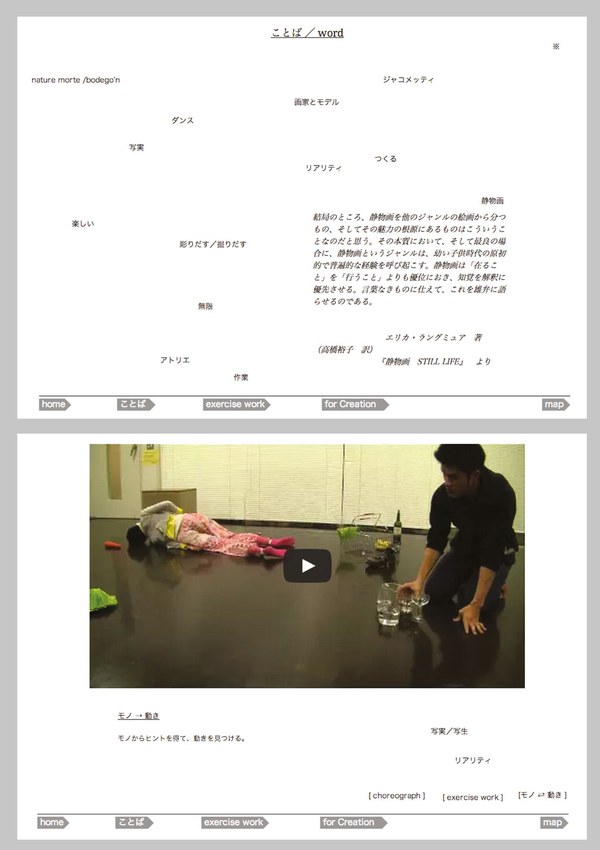

Tsuyoshi Shirai, on the other hand, created a website, which can only be accessed with a particular password. This key is his archive box.

Fig. 8, 9, 10: The ‘box’ of Tsuyoshi Shirai. Courtesy of the artist,

© The Saison Foundation

Natsuko Tezuka decided to utilize language/writing: She wrote a “greeting letter (including a self-introduction and message to those geographically, culturally, temporally, and spatially distant from my own circumstances)”. She also added an instruction manual and a set of “supplementary cards (that may provide hints if a user has difficulty in the process of creation)”. [The Saison Foundation 2015: 25] Zan Yamashita’s archive box comprised technical and playful material: 1 cassette tape recorder (for playing purposes), 1 AC power plug, 1 USB cable, 5 cassette tapes (no. 1-4, 10 Minutes each, no. 5, 20 Minutes), 1 page with text (A4), 1 bag of balloons (15 balloons in 6 colors) und 1 bag of lozenges (strawberry flavor).

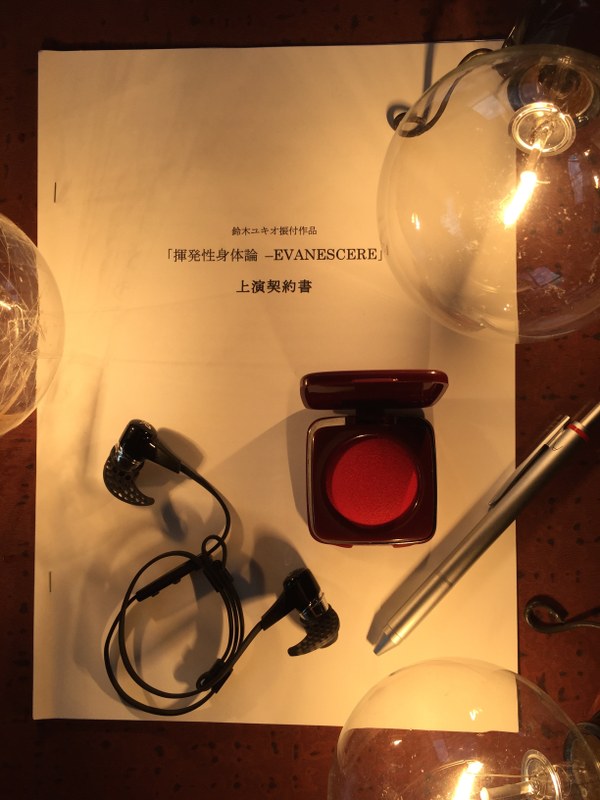

Yukio Suzuki drew up a contract with the user:

Suzuki also drafted a script, which he then recorded: “I attempted to choreograph the user’s way” by instructing the user to listen to the script with headphones throughout the performance. [The Saison Foundation 2015: 21f]

Fig. 11: Yukio Suzuki's ‘box’. Courtesy of the artist, © The Saison Foundation

The rigidity of Suzuki's rules stand in direct opposition to Ong Keng Sen’s original outset—creative commons, copyleft. Ong thus describes Suzuki’s execution of the archive box as an “extremity” [The Saison Foundation 2015: 61]. And yet his approach is similar to the practice museums or collections follow when acquiring performances. The institutions usually make a contract with the artist, confirming the right to perform the piece and closely defining how the performance should be executed.

Zan Yamashita translated the archive box performatively: He “pushed into an extreme physical use, following very obediently all the instructions of the archivist. This discipline was important for him”, Ong elaborates, “Perhaps what is immediately unattractive can also become compelling when both archivist and user become joined in the same spirit on insisting on a very specific approach”. [The Saison Foundation 2015: 61].

Fig. 12, 13: Presentation by Zan Yamashita. Courtesy of the artist,

photos: Koichiro Saito, © The Saison Foundation

PHASE 2

Performing the boxes—Does the word user necessarily indicate a lack of loyalty?[6]

Remarkably, the second phase of Archive Box Project also began with contracts. By handing over the archive boxes – translated into English – to users at the Singapore International Festival of Arts, a contract was confirmed between archivist and user. Questions of ownership, copyright or copyleft, and the “emotional challenges during the process of handing over” Nanako Nakajima spoke about played a key role during this second phase of the project.

The process did not always run smoothly or straightforward; in an interview, Nakajima called some pairings of boxes and users “perfect matches” and confirmed her belief in an artistic instinct that guides the artists in their choice of box. She also conceded that some were “complicated matches” and that there was a “heavy box” with “dark material”.

Padmini Chettur, a well-known and established dancer from India with more experience than the other users, felt quite critical towards the entire project and publicly performed her criticism by not attending group events or taking part in working processes:

As part of the festival’s Dance Marathon, the users presented their performances of the boxes. The archivists were also invited to explain their archives, and text descriptions and photographs of the project were also exhibited. Nanako Nakajima, who was responsible for the development of the second phase of Dance Archive Box, found it important to also give the archivists enough time and space during this phase. The users, however, felt that by scheduling the archivists to perform and present their boxes before them created a sense of secondary performance for the audience, so the whole team subsequently adjusted the program’s order.

All in all, the second phase is not as well documented as the first phase in regard to the working process. The festival’s blog includes some statements by users and a series of conversations between archivists and users.

The Archive Box Project allowed participants to explore the possibilities and potential of dance archives as “meaningful and attractive” tools for new creation. Following the idea of “use it as if playing a game”, the users reflected the concepts of copyleft and creative commons in a range of productive approaches. Factors such as time, quality, quantity, and openness were central issues. The archive became visible as a process of creating distance or even detachment from the artist's own work: archive as a gift, archive as a ‘message in a bottle’, archive stuffed into a shopping bag; archive as a friendly letter, a personal diary recorded on tape or as a contract and rigid set of rules. The concept of passing on all the “ideas, discoveries, and critical awareness” of contemporary dance within the frame of ‘curating potentiality’ led to the questioning of ownership, loyalty and ethics. A further aspect Nanako Nakajima introduced by addressing post-colonialism is cultural exchange. How can specific forms and individual works of a local dance scene (even if the only common denominator is the national funding they receive) become accessible?

PHASE 3

This project should continue to circulate

Nakajima went on to realize a third phase of the project as part of the Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama in April 2016. Once again, mediation, collaborative research and artistic work were juxtaposed. A symposium was held to newly reflect aspects and questions raised during the project. It included international scholars such as the German dance scholar Susanne Foellmer from FU Berlin, who presented her DFG research project ÜberReste. Strategien des Bleibens in den darstellenden Künsten (On Remnants and Vestiges. Strategies of Remaining in the Performing Arts).[7] Participants had the opportunity to reflect and discuss the project from a new, temporally distanced perspective. Nakajima also invited some of the users and presented two performances from Singapore. Furthermore a new set of artists from Japan were invited to work with the archive boxes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ERVL6SQmcYU&feature=youtu.be

Short video documentation of Dance Archive Boxes@TPAM2016, TPAM in Yokohama 2016

At the symposium in Yokohama Atsuko Hisano, director of Saison Foundation, emphasized “it was a goal to create an archive of a foundation”. [Nakajima 2016b] Comparable to the situation of the ‘Freie Szene’ in the German-speaking region, there is no continuous institutional framework that could allow a long-standing archive for freelance artists: this process is solely the responsibility of the artists themselves. “It was the interest of Saison Foundation to make their own archive”, Nakajima elaborates, “not an ordinary one, but to create an artistic archive together with and for the artists”. [Nakajima 2016b] She believes that it was a productive decision of the foundation to leave the results of the archiving process up to the artists instead of forcing the boxes into the foundation’s archive.

Step by step videos and lectures on the Archive Box Project are being published and made accessible. In January 2017, an essay by Nanako Nakajima on the project will be published in the anthology Moving (Across) Borders. Performing Translation, Intervention, Participation (Brandstetter / Hartung 2017). Some of the dance artists are set to continue working with the archive boxes, or to create new ones. The project is continuing to circulate.

Translation: Margarethe Clausen

announcement: https://sifa.sg/2015/sifa/show/archive-box/;

blog: https://sifa.sg/2015/sifa/blog/tag/Dance-Marathon-OPEN-WITH-A-PUNK-SPIRIT/ (last accessed January 2017).