Staging the documentary

Babette Mangolte and the curatorial ‘dispositif’ of performance’s histories

Barbara Clausen (Montréal)

This essay is a reflection on a curatorial concept that was dedicated to the four decade spanning oeuvre of the Franco-American filmmaker and artist, Babette Mangolte, held at the VOX center for contemporary art in Montreal in the spring of 2013. BABETTE MANGOLTE: An Exhibition and A Film Retrospective was Mangolte’s first institutional solo exhibition. It showcased various practices and modes of production inherent to her practice, ranging from early archival works to new site-specific multi-media installations that engaged the viewer in her vast cinematic and photographic works and archives.[1] Part of the curatorial challenge was to consider the complexity of Mangolte’s practice in light of the current practical and theoretical developments that are at the heart of the representational politics of performance art’s past and present.

Since 2005 the understanding that performance art, contrary to its original activist nature, has through its reproduction, archiving, and historization become a classic visual art form.[2] This paradigmatic shift, in both theory as well as practice, has brought forth the contingent nature of performance art, from an authenticity driven live and body centered practice, to a hybrid mode of production that through its ongoing production of multi-media based commodities has ceased to be understood as an ephemeral-driven genre. This re-discovery of 1960s and 1970s performance and subsequently its appropriation is the result of the never ceasing desire for a culture of spectacle and its economy of reproduction.[3] Bringing forth how performance, as a cultural practice of modernity has always been deeply rooted in the inherent tension and codependency between its original performative nature and medial representation. Set at the interface of opposition and cross manifestation, this interest has not only triggered a revival but also its ongoing historicization and institutionalization.[4] In light of the latter ongoing processes Mangolte has not only been recognized as one of the main chroniclers and documentary photographers of the New York performance scene throughout 1970, but has come to be discovered a visual artist in her own right.

Capturing the performance of the vernacular

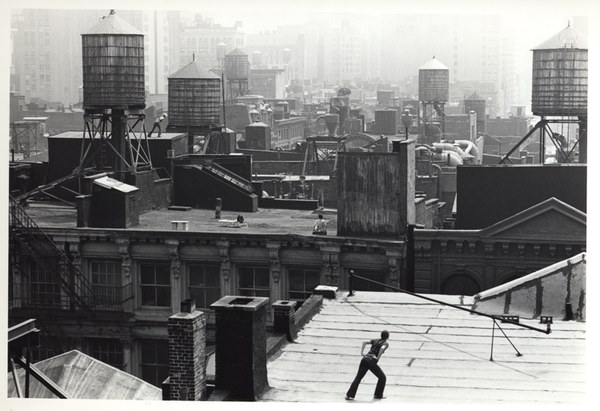

Babette Mangolte, Trisha Brown’s Choreography Roof Piece, 1973,

Photo Copyright © Babette Mangolte

Until the mid 1990s Mangolte was known mainly for her cinematography that she was hired for by a series of avant-garde filmmakers such as Chantal Akerman, Yvonne Rainer, and Michael Snow. After she arrived in New York in the early 1970s, the Manhattan Downtown art and performance scene quickly proved to be an open field to explore, offering the artistic means for site-specific, socially aware and process-based art practices that found their expression not just in live action, but also in text, video, photography and film. Out of interest, as well as commissioned by her peers, she regularly documented the performance work of visual artists such as Robert Whitman, Stuart Sherman and Joan Jonas, choreographers such as Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown, as well as theater directors such as Richard Foreman and Robert Wilson. In her photographs, videos and films she not only captured, but also absorbed and integrated the ideas and the aesthetics of Minimalism, Conceptual Art, postmodern dance and theatre, as well as Structuralist and Feminist experimental film into her practice as a cultural producer. Mangolte engaged and visually coined key aspects of the conceptually driven aesthetics of her time: the rejection of ontological self-reflexivity, the use of operational time, literalism and the effect of space on seeing.[5] She joined the same group of thinkers and practitioners she visually held fast, equally invested in the auto-reflexive deconstruction of artistic processes and new modes of mediation and production. Their historical consciousness and political investment enabled them to recognize the potential of performance art as a time-based and multi-facetted practice. Mangolte has since then been acknowledged as a “first layer of history”[6], a first step in the critical reflection of her image production that helped construct how art history has come to understand performance art. Mangolte’s prismatic role as an image producer, chronicler and agent has manifested itself over the decades as a central point of focus within her artistic investigations.

While photography brought Mangolte to performance art, the subject of photography in her films led her to make work about looking as well as the production of art, mirrored within the work of the artists, dancers and performers she followed.[7] In her early films such as “What Maisie Knew” (1974), “The Camera: Je, La Camera: I” (1977), “Water Motor Trisha Brown” (1978), and “The Cold Eye (My Darling Be Careful)” (1980), the dynamic between the recording apparatus, its subjects and the protagonist are a central factor in her aim for the audience ‘to reassess the way they look at film’. This key approach led her investigation of the audience’s potential for recursive self-referentiality[8] and has also remained an incentive for her installation work as well as her films on the re-stagings of historical performances, such as: “Four Pieces by Morris” with Robert Morris in 1993 as well as her most well known film “Seven Easy Pieces by Marina Abramović” from 2007. Continuing her long term work with the choreographers she documented throughout the 1970s she most recently filmed Yvonne Rainer’s “AG INDEXICAL with a little help from H.M.” and “RoS INDEXICAL” in 2007, as well as Trisha Brown’s performance of iconic choreography “Roof Piece” on New York’s High Line in 2012, originally performed in the landscape of roofs of Downtown Manhattan in 1973. Today, Mangolte is known for her various artistic practices: firstly, her past work as one of the main documentary photographer’s of theatre, dance and performance art of the 1970s in New York, secondly, her ongoing film practice on the re-stagings of historical performance since the early 1990s, and most recently, for her recent multi-media installation work as a visual artist.

Translating time or, how does Mangolte’s work touch upon the contemporary?

Mangolte’s exhibition at VOX and her film retrospective at the Cinémathèque québécoise in Montreal, aimed at presenting a wide scope of her work, ranging from the early archival work to her site specific multi-media installations of the last decade[9]. The aim was to address the multi-facetted historiography of performance art and its rich networks of (past and present) sources and influences. This history has not only inspired an increasingly growing field of research,[10] but is a continuing source of inspiration for an entire generation of artists. While her still as well as moving images reflect a collective imaginary of the aesthetics linked with conceptual and performative practices of the past, they are also an echo of today’s desire to create an ‘aesthetics of timelessness’[11]. This aesthetic of timelessness in her black and white photographs as well as the correlative complexity in depicting the construction of a past reality, which is at the core of her installations, videos and films, has come to stand in for the cultural memory upon an entire decade. These documents, authored by those depicted as well as by those who took the images at the time, give vision to performance histories’ significance in our digitally driven idea of what we consider present and is emblematic for our contemporary desire to look back at the past to better understand the present and the future.

BABETTE MANGOLTE: An Exhibition and A Film Retrospective, installation views, VOX centre de l’image contemporaine, Montréal, January 24 - April 20, 2013,

Photo Copyright © VOX et Michel Brunelle

Given this renewed interest in Mangolte’s artistic network of the past as well as in her own practice, the question how her art installations touch upon the contemporary became the outset of the curatorial concept. This implied less comparing Mangolte’s capacity to articulate and differentiate performative practices, whether dance, theater or visual arts, in her past documentary practice, but rather, three decades later, to look at a growing body of site specifically adaptable multi-media installations. Through a series of six inter-correlating installations, “Looking and Touching” (2007-2012), “Slide Show” (2010), “Rushes Revisited” (2012), “Composite Buildings” (2010), “Eloge du Vert” (2013), as well as a video triptych consisting of “Water Motor” (1978) and two video portraits of Richard Serra and Yvonne Rainer both from 1973 and 1974, the exhibition investigated Mangolte’s intellectual fascination with the time- and site-specificity of performative practices in dance, theater, visual arts, and cinema. The curatorial difficulty of presenting a series of Mangolte’s hermetic installations next to each other, without falling prey to repetition or chronological fatigue, meant allowing each segment to have its own space, kept separate but also adjoined through careful lighting and coloring of the space, linking individual works and ideas, and thereby creating a network of correspondences amongst them. The exhibition’s main narrative thread, questioning how the past becomes part of the present, was reflected within the order of the exhibition layout in three sections. The first, took as its outset how Mangolte correlatively translated and reflected performance art through the various media she has chosen to work with, such as photographs, single channel videos; it culminated in the installation “Looking and Touching”. The second presented her use of the archive as an artistic medium such as in “Rushes Revisited”, and thirdly, her ongoing research and desire to explore the experience and understanding of time and space in “Eloge du Vert”.[12]

Processes of historization : translating archives to installations

Babette Mangolte, Eloge du Vert, 2012, VOX,

Photo Copyright © VOX et Michel Brunelle

Exhibiting Mangolte’s work inevitably addresses the historization of performance art, which, while firmly guarding its claim of a supposedly ‘dematerialized’ art, has become an increasingly image and object-based practice. This paradoxical yet correlative relationship between the live and the mediated, is at the heart of the overlapping revival and discovery of Mangolte’s work and has sparked a critical analysis of the status of the artist’s intention and the authorial claim of the witness to be brought into play.[13] Mangolte’s current art practice is based on her pioneering anticipation, in the early 1970s, to recognize and understand performance art as both an authentic “live-event” as well as a careful concept-based time- and site-specific practice. Mangolte developed an interest in how the avant-garde practices of her peers could be sustained in the future. She was never the author of the works she chronicled, documented, or captured for the camera, as the final choice of which image would be diffused at the time, remained with the artist.

However, the process of historicization reveals a far more complex authorial relationship between the artists’ intentions and the witnesses of their work. As the recognition of a performance is not based on one protagonist but rather constitutes a network of interrelated viewpoints that essentially over time define the authenticity and canonization of a work. For Mangolte this multitude of voices that became audible over time, has allowed her to become part of these complex systems of authorship. Her auto-appropriation of her archive, over the last ten years, is based on the historicization of the aesthetics that have led to the canonization of her past subjects of interest. Consequently, it is not the single image, but the grouping and assemblage of her archive within the medium of the installation, exposing the way she works with her archive as a whole, that constitutes her authorship. This play upon the ambivalence of her own authorship is based on her mastery to translate performance art’s inherent tension between the staging of the documentary and the documentary of the staging[14] in her installation-based works.

In these she not only recognizes the potential of the archive, but reveals and brings forth new voices of the past along her own.[15] Such use of the archive as a medium since the 1990s, beyond its art historical and archeological function as a holder of memory, has triggered new modes of production within the framework of the curatorial.[16] This interlinking of the archival within the exhibition space as a contemporary mode of production, is indicative of the present collapse of the time spans that shape our cultural memory and literally the way we understand and expose archives of the past within the limited spatial and temporal time frames offered by the format of the exhibition. The subsequent acceleration of our perception of the past, is due to three reasons: performance’s increasing institutionalization as part of the work, the growing interest in appropriative practices, as well as contemporary art and art history’s interest in the role of cultural memory and its contingent relationship to collective experience and knowledge production. This folding of time and the vanishing of the traditionally determined three generations it took for a revival of the past to resurface, since the turn of the century has been sped up to the extent that the present immediately is translated into the past. For Mangolte this interest in the cultural archive was an incentive for her to congregate her various modes of production as a filmmaker, a visual artist, and a researcher, and to find her own art by merging the archives of performance art and the medium of the exhibition.

The exhibition as a performative ‘dispositif’

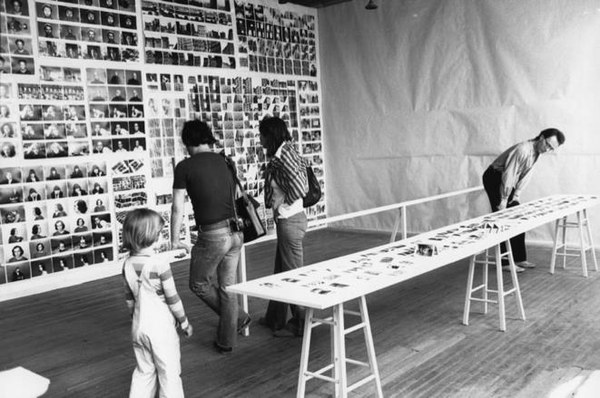

Babette Mangolte, Babette Mangolte: A Photo Installation, “How to Look…”,

exhibition view with public at P.S. One, Old Wing, Room 204, Long Island, New York, May 11-28, 1978, Photo Copyright © 1978 Babette Mangolte

Babette Mangolte, Rushes Revisited, P.S. One Dismantle, 2013, installation view at VOX, Photo Copyright © VOX et Michel Brunelle

Babette Mangolte, Looking and Touching, 2007,

installation view at the Hansard Gallery Southampton,

Photo Copyright © 2007 Hansard Gallery Southampton

An interest that also echoed her own explorations of ‘how we look’ at art, as a topic, from own films of the 1970s, one that she was now able to address in her artistic practice. In installations such “Looking and Touching” 2007 or “Rushes” 2008 the stagings of her archive become a key part of her artistic production and reflection on the work processes themselves. Almost exclusively showing in large-scale group exhibitions[17], Mangolte systematically uses the format of the exhibition as a situational structure, a time-space in which she can address how we perceive and therefore experience knowledge as an integral part of an aesthetic experience.

As such they not only signify her own relationship to the experience of duration, but show how different formations of time acknowledgement, like episodic memory, which is the registration of an immediate experience, and the semantic memory, the process of acquiring knowledge and therefore understanding what something is about, feed into collective memory.[18] Taking account of the changing sensibilities in the relationship to the semantic and episodic experience of time, the exhibition not only focuses on Mangolte’s past, but rather her recent practice. This meant engaging in Mangolte’s continuous re-appropriation of her own documentary photographs, videos and films in her installation-based works.

She creates a ‘mise en abyme’-like exhibition within the exhibition that reflects the epistemology of performance art by deconstructing its medial particularity. This is most apparent in the four existing versions of “Looking and Touching”, through which since 2007, the exhibition space is turned into a site of expanded perception that allows for the artist’s archive to become a recursive self-generating medium, which, according to Ludwig Jäger, brings forth the semantic peculiarity (Eigensinn) of the chosen medium[19] – a media specificity that becomes visible through its production and simultaneous reproduction. The staging of Mangolte’s own archive from the 1970s, the period in which she herself as a cultural producer remained largely invisible, while taking her most emblematic photographs, becomes the means for the artist, four decades later, to be granted visibility within the shadow of performance art history’s historicization.[20]

The visual cross-mirroring of both past and present production processes inherent to taking photographs, shooting a film or creating an exhibition, have been at the center of Mangolte’s own work since the 1970s, most emblematically in her two first feature films “What Maisie Knew” and “The Camera: Je, La Camera: I”, both of which she shot in the mid 1970s in New York. The parallel existence of different practices is not a retrospective revelation but was key to her practice from early on. Thinking about the overlapping circumstances of experiencing, producing, and thinking about art, was at the center of Mangolte’s first exhibition “How to Look…” at PS1 New York in 1978. This first small-scale exhibition has come to determine the aesthetic dispositif of her art installations until this day,[21] and has over the last decade served her as a template to develop a particular style and composition of exhibition installations, as visible in “How to Look…”, “Presence”, “Looking and Touching” as well as in “Rushes”. Despite the different ways in which the gaze and thereby presence of the viewer is addressed, Mangolte’s often space filling installations expose the status of her first exhibition as a medium, revisiting the basic layout of her first exhibition.

The correlative affinities of an archive to its spectacle

The juxtaposition and appropriation of the cinematic and the curatorial and the correlative translation of one within the other, gave her the space to develop an aesthetic dispositif, to frame and therefore stage her own archive within the theatricality of the exhibition space. Mangolte echoed these processes, in a sequence in the film of “Rushes”, which is an integral part of her installation under the same name. We see the destruction of a large photo wall that was created with hundreds of photographs. An assemblage of still frames from her film “The Camera : Je, La Camera : I” mixed with private images, recorded in the process of its de-installation and removal from the viewer’s gaze. This particular filmic staging of Mangolte’s first exhibition, as a time bound space, becomes the outset of Mangolte’s future explorations of the format of the exhibition within the medium of film. The installation of “Rushes” is a portrait of an exhibition within an exhibition. Crossing and translating the medial constraints from a performance, to film to an installation, affirms and at the same time puts on display the complex economies that determine the symbolic systems generated through performance art’s contingent semantic particularities.

Babette Mangolte, Looking and Touching (2007),

installation view at VOX, Photo Copyright © VOX et Michel Brunelle

In “Looking and Touching”, another installation presented at VOX, one could see on one hand, the cinematic space explored by Mangolte within her films and on the other, the immediate performative space of the exhibition. The merging of these two viewpoints calls out and thereby affirms its continuous translation of past forms of existence into the presentness. In “Looking and Touching”, the barrier between the spectators and the photographic collages on the wall simulate the distance between the past and the present. This dialectical play of near and far, of accessibility and of constriction, and the integration of texts within the installation not only became a staple of her aesthetics, but integrated the viewer to become part of the installation and the evaluation processes’ institutionalization of the images and objects exposed. Played out within the given exhibition context at VOX and situated within a series of the artists’ installations, the viewers became active witnesses to the artists’ ongoing process of retrospective analysis of her own work within the present.

Mangolte’s capacity to differentiate and articulate performative practices through their transcription into various visual media, explores the push and pull between the immediacy of the archive and the spectacle of cultural memory. Mangolte’s interweaving of the archive with the exhibition as two types of interrelated media, offers the visitors the opportunity to understand and experience how performance art has developed from an artistic form of expression rooted within the idea of the “live”, to a hybrid media and a discursive practice. A genre and medium increasingly important for a wide range of cultural producers engaged in conceptual and critical art practices who might not consider themselves as performance artists per se but who rather choose to work within the realm of performative practices.

Barbara Clausen is a professor for performance history and theory at the art history department at the Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada. She received her PhD in Art History from the University of Vienna (Austria) on the subject of "Performance Art: Documents Between Action and Spectator. Babette Mangolte and the Historicization of Performance Art" in 2010. Since 2004 Clausen has been a research fellow at the IFK in Vienna, the Cinema Studies Department at New York University, and the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, at Concordia University in Montreal. Since 1997 she has worked at Dia Art Foundation (New York), DeAppel (Amsterdam), and Documenta11 (Kassel) and has curated a.o. the exhibition and performance series After the Act (2005), Wieder und Wider/Again and Against (2006), and Push and Pull (2010/2011) with Achim Hochdörfer at the MUMOK in Vienna and TATE Modern in London. In 2012 she curated the performance, exhibition and lecture series Something to Say, Something to Do as well as the recently opened exhibition on the work of Babette Mangolte for VOX, centre d’art contemporain, in Montréal. She is currently working on a two part exhibition program on space and identity, entitled Stage Set Stage at the SBC center for contemporary art in Montréal for 2014 and continuing her research on the historiography and institutionalization of performative practices in the arts.