Reclaiming the Invisible Past of Eastern Europe

An interview with art historian Ieva Astahovska, head of the research study on the nonconformist art heritage of Latvia’s Soviet years.

by Zane Zajanckauska (Riga/Leipzig)

“People in Cages” (1987), Performance by Sarmite Māliņa, Sergejs Davidovs, Oļegs Tillbergs; © LCCA

“The Documentation and Preservation of the Nonconformist Art Heritage of Soviet Years” is an ongoing research project in Latvia, commissioned by the Ministry of Culture and aimed at creating a contextual background for the collection of the future Museum of Contemporary Arts. “It is rewriting history, a process that is taking place in the East and the West simultaneously” says Ieva Astahovska, art historian, head of the Information and Documentation Department at the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Arts www.lcca.lv and a head of the research group consisting of around 20 researchers working on this topic in Latvia.

This Latvian research is now related to similar projects in Hungary (tranzi.hu), Lithuania (National Gallery of Art), Poland (Wyspa Progress Foundation) and Estonia (Estonian Institute of Art history) in the EU-financed project “Recuperating the Invisible Past”, planned to result in a joint conference in 2011 and ongoing collaborative projects in the very near future. We asked Ieva Astahovska about the contained term “nonconformist” in the context of the research, the role of performance and its documentation in Latvia from the 1960s to the 1990s and how the existence of isolated information formed its own history and context of performance art in Latvia.

Could you briefly describe the subject of the research project? How the “nonconformist” art scene is defined and regarded now that a few decades have passed?

The study falls within the current tendency to investigate the unknown history of Eastern Europe and the processes of rewriting history, which is happening just as intensely in both Eastern and Western Europe. By documenting the Latvian heritage of nonconformist art, we wish to record the events and processes in art that never appeared in official history. It did not necessarily always happen because of the political context of a particular piece of art; often enough interdisciplinary processes were not recorded as art events simply because they did not fit into either of the categories of traditional fine arts or theatre.

The term „nonconformist” in the title is more like a formal adaptation in the context of our study, because the very notion of nonconformity is rather controversial, especially in the Latvian context. If, say, in Russia nonconformist and official art scenes were clearly segregated, then in the case of Latvia we can only speak a sort of semi-nonconformity. Almost all the artists whom we mention in the context of non-official art were at the same time members of the Artists’ Union of Latvia. Most of them had either graduated from or at least studied in the Art Academy of Latvia, and almost all of them participated in exhibitions, which were not apartment exhibitions as in Russia, but more or less official institution exhibitions.

In the context of our study, nonconformity is less related to the political message than to the form of the works: experimental, avant-garde, different from the dominant doctrine. The interdisciplinary aspect of the art processes is also very important, because precisely the interdisciplinary events were not mentioned in the official chronicles.

This study covers the period from the 1960s to the 1990s; however, we examine the second half of the 1980s in less detail, because it has been researched thoroughly already in our previous research projects.

What was the role of performance art in this unofficial art zone?

Performance art most directly belongs to the nonconformist zone and does not appear in the official event chronicle, because nothing of that kind could be openly expressed.

In this study the concept of performance art includes performances starting from informal apartment happenings, like those by A. Grīnbergs[1], where he invited a lot of people, sometimes complete strangers, and staged situations, spontaneously or according to a pre-made script, often perceiving and calling it a „photo shoot,” not a performance; we also consider pantomime and motion theatre as performance arts. Pantomime or motion theatre functioned as a kind of amateur theatre, with a director, choreographer, a costume artist and a troupe of actors, often possessing some basic acting skills, though nonetheless, it was not theatre. In the performances of pantomime and motion theatre, movement has considerably more expressive meaning; there is no literal, illustrative action. Interestingly enough, during this period of time movement became an important means of expression and attained its position not only in performance arts, but also in sculpture and painting.

One of the performances by Andris Grinbergs: “Model and Others”, 1988; © LCCA

Can we speak of total isolation of the evolution of performance in Latvia from the development of performance arts in Western Europe?

Absolutely, Western performance art is closely linked to conceptualism, to the idea of art being made not only in the classical sense, but also to protest against the commercialization of art, putting it inside the white cube. In Latvia there was almost no connection to this context at all. In the case of A. Grīnbergs, there was opposition to the system and authority, but more in a playful way; it was not a political intention, but rather „the art of life,” creating one’s own miniature life without any political message.

Although artists in Latvia have been influenced by the West, these influences almost always stay on a merely visual level. Insofar as we have spoken to artists, they all say they have been looking at Polish art magazines, but merely looking at, not reading them. Discourse space did not exist here in Latvia (there was even a certain allergic reaction to it, due to the ideological rhetoric of socialism). Theoretical discussions of ideas barely took place at all. Influences mostly stayed at a metaphorical level. Seemingly very little was needed at the time – a small picture had a literally electrifying effect, but the conceptual context was lacking. Speaking of performance, many cite Beuys as a very important artist for them, although they only take the surface and fail to develop the message and ideas that were important for Beuys.

In the 1980s some political social contexts did emerge to some extent, although they are nonetheless very metaphorical, to the point of being paradoxical: for example, performances that can only be interpreted politically, such as „People in Cages” by Māliņa, Tillbergs and Davidovs during the Art Days of 1987[2]. When we talk to them now, Tillbergs allows it to be interpreted politically, while at the same time Māliņa or others insist that it had nothing to do with politics, that they were not interested in any kind of political articulation. The whole matter is vague and blurred in the visuality and metaphoricity of art.

At the time the dominant opinion in Latvia was that an artist is neither a journalist nor a politician; he or she is an artist precisely for the reason of being associative.

You have already mentioned that performances were sometimes staged photo sessions. What was the overall role of documentation in the performance scene of the 1960s – 1980s?

Our study is mainly based on current history, i.e. conversations with artists and retold events. For many events no visual evidence has survived, because at the time no one found them particularly important.

Performance as such is quite elusive, and furthermore, there were many spontaneous events that could be considered performances according to the standard definition; however, the people involved do not define it that way themselves, or they label it ”the art of life.” For example, the graphic artist Māris Ārgalis, referred to by literally everyone as a nonconformist (also in the traditional sense, since he continuously confronted the powers of authority and ideology), had this exhibition “Models” in 1976 at the House of Science, which at the time used to house exhibitions slightly less restricted by censorship. The night before the opening of this exhibition his friends gathered at the place, and there were pictures with all of them hanging in the cloakroom as abandoned coat hangers. At the moment it was a spontaneous action, and when I asked one of the participants whether it was a performance or not, he replied that of course it wasn’t; it was just fooling around.

Nevertheless, there is also another aspect. Performance happenings have often been so expressive in their visuality that they have served as source material for the independent work of photographers. For example, Zenta Dzividzinska[3] has frequently photographed pantomime; her work is very expressive, with interplay of black and white hues, so common in pantomime. Another example would be Laimonis Stīpnieks[4] who has photographed performance art quite often. And in those photographs you see a piece of art by Stīpnieks, not the performance itself, but its documentation; he has added so much of his own perspective that the result has outgrown the original subject (performance). Furthermore, it has not only occurred in photography. For example, Atis Ieviņš took up silk-screening under the influence of Warhol and has also used Grīnbergs’ happening photographs in his prints. Also, Jānis Kreicbergs, a fashion photographer very much integral to the official zone at the time, collaborated with Grīnbergs and photographed Grīnbergs' wife Inta in a performance, making music with elderly women of the Livonian national minority[5]. And then there is a picture of an old Livonian woman with an emphasis on the ethnographic moment. It played no important role in Grīnbergs’ performance; however, the photograph changes the context and „being Latvian” becomes the main message.

In addition, you are in charge of the library of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, which also serves as a centre for documenting art. Is the significance attached to the documentation of performance art changing at the moment? For example, are apartment performances, currently gaining popularity in Riga again, deliberately documented?

Well, it is a very good idea. Actually no, we don’t do it, although we do try to record art events and processes, but not apartment performances. I think that modern times are far more thorough in this respect anyway. There is always someone who records it just out of curiosity and the performers themselves are aware of their performance as an intentional action.

Back to the study: could you briefly describe the process and expected result of it?

We are a rather large group of researchers and we have divided the areas of study among ourselves, ensuring a collective process through regular meetings. We investigate personalities, events and processes, largely based on profound conversations with artists. One of the results of this study is going to be a chronicle with official events listed, but with the unofficial part particularly highlighted. And this material will be of use for more conceptual conclusions.

The ultimate outcome of this study will be an exhibition by the end of 2010 and a conference in 2011, where we will try to combine the material of our Latvian study with parallel processes in other Eastern European countries which also are experiencing the processes of rewriting history. We are already cooperating with institutions in Lithuania, Estonia, Poland and Hungary. At the same time, we are trying to integrate the Latvian scene into the overall picture, since Latvia is, even in the Eastern European context, fairly marginal. Another important aspect is to bring the Eastern European dimension into the Latvian context, since despite being quite integrated, we still live in a very regional way.

See also: Ieva Astahovska, Non-conformism, "(Re)writing" and "The Author of the Quixote". In: Studija No. 2, 2009 http://www.studija.lv/en/?parent=577

The exhibition, showcasing the results of research, is planned to take place in Riga Art Space at the end of 2010, under the title “un citi” (literally, “and others,” referring to a list of participants, which only mentions some of them with the others always included in the abbreviation “etc.”).

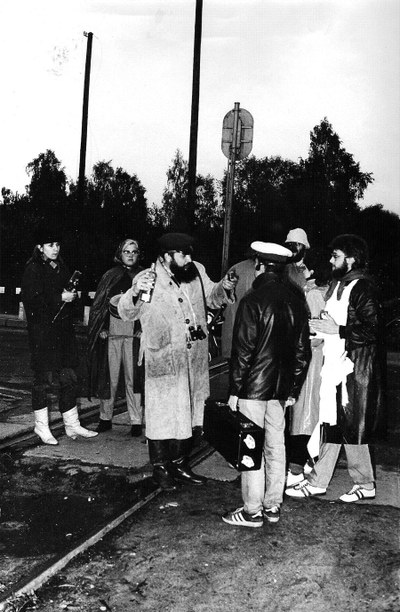

Walk to Bolderaja, a performance by group “Workshop of Restoration of Unfelt Sensations”. 1980s; © LCCA

Ieva Astahovska, art historian, is working on her PhD at the Latvian Academy of Arts. She works for the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Arts, as well as lecturing at several Latvian universities. Her art critiques and research articles on 20th and 21st century Latvian art have been published in numerous printed media catalogues, symposiums, etc.

Zane Zajanckauska, cultural project manager, received her MA at the Latvian Academy of Culture. She worked for the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Arts until 2009; since then she has worked at the Museum for Contemporary Arts in Leipzig, with a Robert Bosch Scholarship for Cultural Mangers from Eastern Europe.

[1] Andris Grīnbergs (1946) – a Latvian performance artist, a prominent figure in the performance scene of Latvia in 1970s-1980s.

[2] „People in Cages” - a performance by Latvian artists Sarmīte Māliņa (1960), Oļegs Tillbergs (1956), Sergejs Davidovs during the Art Days in one of Riga’s central squares: a man dressed in Soviet Army uniform sleeping in a metal cage.

[3] Zenta Dzividzinska (1944) – Latvian photographer, member of the unofficial creative interdisciplinary Riga.

[4] Laimonis Stīpnieks (1936) – Latvian phtographer and architect.

[5] Livonians – a historically distinct ethnic group in the territory of Latvia, already assimilated in the 19th century. Nowadays only very few remain on the west coast of Latvia, where performance artist A.Grīnbergs used to have a house and staged some of his performances.