Creating Own Context(s) - Meeting the Challenge of Participation

The Projects by the Collective IRWIN

Interview with Miran Mohar & Borut Vogelnik

by Veronika Darian (Leipzig/Berlin)

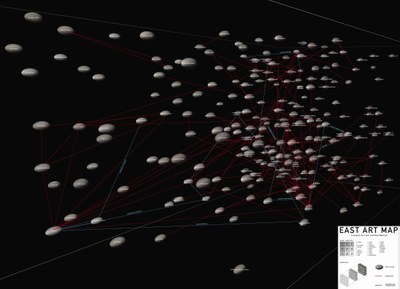

IRWIN, Map of Eastern Modernism, 1990

The Slovenian painters’ collective IRWIN consists of five artists: Dušan Mandić, Miran Mohar, Andrej Savski, Roman Uranjek and Borut Vogelnik. The group was founded in 1983 in Ljubljana and IRWIN was also a co-founder of the NSK (i.e. Neue Slowenische Kunst) organization. In addition to other activities, IRWIN has been engaged in a series of projects of active and concrete intervention in social and historical contexts in the decade that redefined the status of art in Eastern Europe. Ever since IRWIN confronted the art world with the EAST ART MAP (EAM), a map of artworks from Eastern Europe between 1945 and 2000, various provocative questions have come up: regarding the selection within curatorial practice, the intrusion of artists into the field of art theory and historiography, the gap between the seemingly dominant Western and supposedly backward Eastern art market or – not least – the challenge of the participative integration of art observers and users. The EAM project challenges the art systems in the East as well as in the West by the will and the task to write its own art history in relation and opposition to the western attempts. It is deeply rooted in the social and political changes of the 1990s. (www.eastartmap.org)

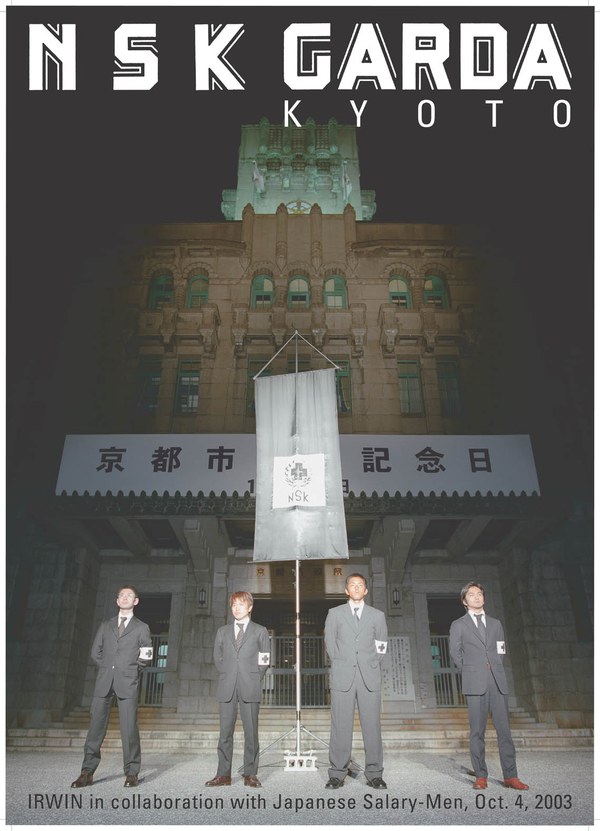

In 1992 the NSK proclaimed the NSK State in Time, since then issuing passports and opening temporary embassies in different cities all over the world. Many people from diverse countries have already applied for the NSK passports, particularly from African countries in recent years. (http://times.nskstate.com)

The work on the EAM project appears to have stagnated. Nevertheless, the issues raised seem to be surfacing in current projects of IRWIN, for instance NSK State in Time and its diversifications.

IRWIN, East Art Map 2005

The EAST ART MAP (EAM) project started in 2000 and was displayed on various platforms (the EAM website, the East Art Museum exhibition, the EAM book, the Mind the Map! symposium…). Was there a common goal for all these formats from the beginning?

Miran Mohar: The EAM project consists of several phases:

In 2000 IRWIN, in collaboration with New Moment (Ljubljana), invited a group of art critics, curators and artists from different ex-socialist countries in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe to select and present up to ten crucial art projects from their countries and contexts that had been created over the past 50 years. In this way, basic data on approximately 220 artifacts and projects were collected and presented on a CD-ROM (2002) and in a special issue of the New Moment magazine that same year.

The next step was to put the EAM selection on the Internet and open it up for contributions by users who could propose the artifacts, events and projects they considered significant. The general public as well as specialists were invited to provide additional data. The international EAM committee then chose additional works from these proposals.

The EAM book is derived from these two processes, including all the reproductions of the artifacts selected, as well as additional texts about each artifact and artist. The second part consists of 17 comparative essays. From the very beginning, it was meant to be an integral part of the EAM project.

An important part of the project was also the symposium called Mind the Map!, in which young researchers from Eastern and Western Europe discussed the topics of the EAM. The symposium, which took place in Leipzig in 2005, was prepared by Marina Gržinić, Veronika Darian and Günther Heeg.

At the initiative of Michael Fehr, the East Art Museum exhibition of works created between 1950 and 1980 and selected from the EAM database took place at the Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum in Hagen 2005.

Each of these platforms had a specific function with the common objective of taking the first steps in constructing the previously non-existent art history in Eastern Europe.

Understanding the project as a question – who ought to answer?

MM: We initiated this project because no specialists or anyone else in the field had done it. We still hope that this will happen, that art historians will do it much better, that the answer will be other books on this topic. But this process is rather slow. It’s similar to constructing all elements of the art infrastructure in most of Eastern Europe. The elements can’t be established overnight. On the other hand, we are happy to see many names from the EAM selection included in important international exhibitions, such as the Venice Biennial and last documenta XII. It’s very encouraging to see that a very good and useful book on art from EE written by Piotr Piotrowski appeared in English translation last year.

Understanding the EAM project as an open invitation to criticism – what ought to be questioned the most?

MM: About two fifths of the works proposed by the selectors within the framework of the EAM project were totally new to me and, as I know from our talks, to my colleagues as well. And if this is the case for us, who have been active in EE quite a lot, you can imagine how this is for others. There are quite a number of works which show that on the other side of the Iron Curtain an artistic practice was developed in which the conceptual line was particularly strong and significant. It can be seen that some artists were working on original concepts surprisingly early and this became evident from the EAM outcome. Of course, in-depth research and comparative studies are necessary to place these artistic practices in the global context, which is exactly what we hope will happen. But this exceeds the framework of the EAM project and our capabilities.

How did you select the selectors?

MM: We selected them on the basis of our knowledge of professionals from Eastern Europe. Since the end of the 1980s we have had a vivid communication with numerous artists and curators from Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary and all the countries that have emerged from the former Yugoslavia. We chose the selectors according to their professional skills and their knowledge of the local and international art scene. Most of these people were very active in their respective places and some of them also internationally. The ones we didn’t know were proposed by professionals whose opinion we trusted and we selected them from several names.

Was it essential for the project to be started by a collective?

MM: I think this was very important because the project is very complex and not easy to produce. In general a group/team can implement and produce such a project much more easily. It’s true that as a group we have more contacts in different parts of EE (selectors, theoreticians, co-producers and publishers) and I believe that such a project wouldn’t be possible without these connections and mutual respect. IRWIN almost had to reorganize itself during the project into a small foundation in order to deal with the production and organizational issues of such a complex project.

The EAM project seems to oscillate between being an art project, an attempt at historiography, a particular selection and a participative structure.

Borut Vogelnik: It is so easy to get subsumed and labelled today that I’m pleased by the persisting questions about how to understand and list EAM. On several occasions different people have asked us: “EAM is an art project, isn’t it?”, as though it were necessary to exclude the possibility that it is not an art project, that it is for real. Aside from the fact that it is much more likely for an artist to hear that his project is not art, it is quite amusing that there is a book on art where artists are selected by selectors of high reputation, with accompanying essays written by specialists some of whom have achieved international fame. It is a book which was published by Afterall and distributed by MIT Press and is considered to be a piece of art.

Basically all we did was to connect all elements and organize the process, to do what a publisher would usually do. We are really proud and grateful that all of the invited specialists accepted being part of such a risky operation. They were the ones who literally wrote the book. If you consider it just a book and exclude its possibility of being an art project thus remaining with a historiographic perspective, a particular selection and a participative structure, everything seems to fit perfectly well. What seems to stand out is a wish to perceive it as art and not the other way around. It is interesting that art is used as a euphemism to delineate something as playful, not serious, a joke. – And if not exactly taking them as jokes, disbelief in the potential to affect reality was fairly usual when similar projects were in question back in the 1990s.

In the East it is still possible to intervene in the field of articulation as a “private individual” on levels that are elsewhere in the exclusive domain of institutions. Such interventions are, thanks to already familiar models, so much like painting from nature that we are prepared to see them, in their uniqueness and beauty, as artifacts.

(a book edited by Irwin, published by Afterall Books and distributed by MIT Press, 2006)

Could you explain your idea of the EAM as a project regarding theory as well as practice between local, regional and international agencies?

BV: In fact it is possible to trace a continuous line of motives and questions that resulted in EAM back to IRWIN’s beginnings in the first half of the 1980s. But the decision to start the EAM project was directly connected to a series of projects conceived for the purpose of understanding and at the same time interfering with the art system and its practical implications.

We have published five books, which were the final products of five projects from the period of 1990 to 2006, the year in which EAM was published. All five projects were focused on reflecting on the modern art of the East, and from the very start all of them included the production of a book as the ultimate goal and central artifact.

Kapital was the start of our work. The project dates back to the period of the socialist system, which had already been transformed by the time we published the book. Meanwhile, EAM was published in its complete version at a time when Slovenia had already become a full-fledged member of the European Union. These projects thus literally connect the beginning and the end of the period we call “the time of transition”. But this external correspondence is not the only thing that links this series of projects with the concept of transition. Transformation is the theme and the content of the Retroprinciple book series.

Already with the Kapital, our suspicions were confirmed with regard to the difference in the way the art systems operated in the East and the West. We were indeed confronted with ample evidence that, beyond a shadow of a doubt,such differences did exist in a whole range of empirical facts and details that shaped the conditions of production. A difference in conditions is reflected in a different kind of production. The Retroprinciple book series begins with a thesis about the specific conditions of art production in the East. Through travels to Moscow and across the USA we tried in many discussions to articulate this difference, which in the Interpol project materialised as an open conflict.

Eventually it became apparent that one of the key differences was precisely a difference in the regulation of communication, articulation and inscription — which is something that the Retroprinciple books have, to the best of our abilities, attempted to thwart. It follows thus that this series culminated in EAM, which is a synthesis of the experiences and realisations accumulated over the course of the previous projects. EAM deals with the most basic level of organising information, the drafting of a simple chart of the most important artworks and artists from the area of Europe’s East in the period from 1945 to 2000.

In Eastern Europe there are, as a rule, no transparent structures in which those events, artworks and artists that are significant to the history of art might be organised into a referential system accepted and respected outside the borders of a single given country. Instead, we encounter systems that are closed within national boundaries, most often based on a rationale adapted to local needs, and sometimes even doubled so that alongside official art histories there are whole series of stories and legends about art and artists who opposed the official art world. But written records about such artists are few and fragmentary. Comparisons with contemporary Western art and artists are also extremely rare.

In the first place, a system that is so fragmented prevents any serious possibility of comprehending as a whole the art created during socialist times. Secondly, it represents a huge problem for artists who not only lack any solid support for their activities, but are also, therefore, compelled to navigate between the local and international art systems. Thirdly, such a system impedes communication among artists, critics and theoreticians from these countries. Eastern European art requires an in-depth study that will trace its developments, elucidate its complexities and place it in a wider context. But it seems that the immensity of such a project makes it very difficult to realise, so that any insistence on a complex, unsimplified presentation inadvertently results in having no presentation at all.

The aim of EAM is to display the art from the entire territory of Europe’s East, to take artists out of their national frameworks and present them in a uniform scheme.

What is the impact of the EAM project in countries other than Slovenia?

BV: The Press, included in many different presentations and exhibitions, noticed EAM and we were invited to present it at numerous conferences and round tables. If I judge on the basis of what I have heard or read, the response has usually been positive, although on a few occasions serious doubts have been expressed as well. Probably the most interesting of these doubts concern the question of whether dividing East and West has any sense now that we are united at last.

At the beginning of the 1990s just after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a feeling of insurmountable distance was transformed into a general wish and hope that the two halves of Europe might join together as soon as possible. Both sides had the aspiration, at least declaratively, to eliminate the differences between them as soon as possible and to establish “normal” conditions.

It is as if, among all the various activities in the East that have been involved in the difficult process of transformation, only the artistic sphere has been able to become unified overnight so that it has never been possible to articulate the difference. At the time that it would have made sense, there was no interest, and it is only possible now that the difference has become obsolete. In this perspective it is understandable that speaking about East(ern European) art and not about art from the East was not really popular at the beginning of the1990s.

During the last couple of years the situation has changed. Collections dedicated to art from the Eastern Europe and organising archives about it (for instance Erste Bank Collection from Vienna) have been established. Certain newly established museums for contemporary art in different parts of the former Eastern Bloc are articulating art historical narratives and presenting art collections that are not confined to the borders of national states, but cover larger territories, as in the case of the newly opened Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, which presents art from the territories of former Yugoslavia. There are quite a few exhibitions in preparation that are going to deal with certain aspects of East(ern European) art in the near future. One is the Internationale, a joint project of four museums initiated by the Museum of Modern Art in Ljubljana, dedicated to conceptual art in the former Eastern Bloc, and another is an exhibition titled “Former West” to mention just two of them.

The EAM project itself is not dealing with the difference at all. On the contrary, it is entirely dedicated to the art of the East. The perception of East art has changed substantially in the last twenty years and EAM should be seen as part of this development.

What about the continuation of EAM, its sustainability as it were?

BV: Let me quote the standpoint that we took in relation to EAM at the time it was produced: “We do not seek to establish some ultimate truth; on the contrary, our aims are much more modest and, we hope, more practical: to organise the fundamental relationships between Eastern European artists where these relations have not been organised, to draw a map and create a table.

If experts from the field of art history and theory, or indeed anyone who understands these matters better than we do, should find that EAM is somehow lacking or in many ways superficial and imprecise, or that it does not reflect the image that in their opinion should be reflected, then we would have to agree. We have no intention of stubbornly insisting on being right. Just the opposite, since we are well aware of the complexities of the problem we are tackling, as well as of our own limitations. Moreover, we do not think it wise, or even possible, to outline such a system once and for all, and we will, of course, be delighted if someone corrects our mistakes.”

The long years of isolation of the national art systems have led to many “arrangements” (to put it mildly), so that when the local system is forced to confront the international system various things can happen: certain pillars of national art might lose their shine or the symbolic order might be threatened. Local mythologies, which, as is typical of mythologies, do not support critical examination or comparison, have become deeply interwoven into the social fabric of the individual countries.

EAM, the chart itself, should not be considered of major importance regarding sustainability, no matter how good or bad it is. Opening up a public discourse on art with its reflection, comparison and validation, not only confined to the local borders is far more promising.

Imagine you started the EAM project in 2010 – would you choose the same approach and the same structure?

BV: The EAM project is based on our experience with the international art system gained through continuous exhibiting outside Slovenia and Yugoslavia from the mid 1980s on. It became clear to us that systems closed within national borders, most often based on a rationale adapted to local needs, represent a huge impediment for artists, who, deprived of any solid support for their activities, are compelled to steer between the local and international art systems. It presents a major block to communication among artists, critics and theoreticians from these countries.

We, as artists from the East, were interested in helping to change it.

I would like to stress that EAM is a result of concrete circumstances. Even the production possibilities and the rhythm of execution of different parts were not decided by us but arose out of necessity. The project is so deeply tied to reality, so truly targeted to be functional that it is really difficult to speculate as if it did not exist.

Does it still matter to be Slovenian – as artists or as an artists' collective?

BV: To be Slovenian and Eastern never mattered to us in a yes-no manner, deciding between yes and no, being Slovenian or not. It mattered and still matters in the manner of accepting it as it is, taking it as given. We were always fairly clear about it. Let me quote one of the sentences dealing with the topic: ’’We decided on the East as the field of reference for our activities out of the following considerations: because we are from the East (although such an assertion is extremely unpopular in Slovenia, it is nevertheless true that, despite certain differences, we were part of the so-called East for nearly half a century; we shared with the East a whole range of characteristic features in the way our society was organised, including the way the operations of the art system were organised; and last but not least, external perspectives also placed us, as a rule, in the East); because even if we wanted to, we could not escape it; because it is impossible to establish communication without first articulating your own position.”

It was exactly on the basis of accepting what was given that we built NSK, first as a group and later as a “state in time”. It seems we have good chances that it is going to matter to be NSK artists as well.

How would you describe the connection as well as the differences between EAM and other projects of yours?

MM: These are two separate projects, but they are connected because they both touch on the issue of how reality is constructed.

BV: It was in 1992 that the NSK State in Time was declared as a development of the NSK collective from the 1980s. In 1993 we started to issue passports and the number of citizens slowly but steadily grew.

MM: The citizens of the NSK State in Time took the initiative and started to use the conceptual frame of the NSK State. A few years ago, they started to produce their own projects and artifacts related to NSK or the NSK State independently from the NSK groups. One of its citizens, Haris Hararis, who is based in Athens, started the project nskstate.com in 2002. This site has become a meeting point of NSK citizens (who also moderate the site) and the most significant centre of their activities. Christian Macke opened an NSK library in Maine (US). For a few days every week he transforms his house into a public place where you can read NSK-related literature and watch NSK-related films. Some people from Iceland opened a temporary NSK Embassy in Reykjavik a few years ago and did a performance in collaboration with the Icelandic coastal guard, just to mention some examples.

Since 2007 a few thousand of Nigerians have applied for the NSK passport and, as we understand from their e-mails, some of them use the NSK passport for travel in Africa. So the NSK State is alive because its citizens apparently need such a form of state and because they are actually using it. It seems that the NSK State is a practical tool for the construction of social relations and communication with other entities (which was our idea and hope from the very beginning). Of course, it was impossible to predict to what extent the NSK State would come to life, fulfilling the needs of its citizens. What more can we, as artists, wish for?

IRWIN, NSK Passport (1993)

The requested participation of observers and users has apparently turned into a self-conscious (friendly) takeover. Which of these processes still remain in the hands of the ‘initiators’? And how you deal with this sort of ‘disempowerment’?

MM: When NSK citizens apply for the passport, they are not asked to fulfil any obligations to the NSK State. They can use their passports and citizenship however they wish. Passport holders began to communicate among themselves on their own initiative. Since they seem to recognize the NSK State in Time as a common space with which they can identify, thereby relativising their identification with their national states (as some of them have stated).

It’s important to stress that when we found out about the nskstate.com, which to most people looks like an official NSK State site, we didn’t react restrictively. On the contrary, we hailed this move and have been sending information about different NSK groups’ activities. It was a decision, which we discussed and took a standpoint on. This site, which is in hibernation at the moment, was the only NSK State site for a long time. We also started to collaborate with the nskstate.com and its founder Haris Hararis, with whom we did the work Words from Africa. The first NSK citizens’ congress was initiated and proposed to some NSK citizens by IRWIN. They were interested in the idea and they do the programming and selecting of delegates. IRWIN is now involved only in the production issues. The Congress Organizational Committee has also invited all NSK groups to participate in the congress. Maybe the congress will find answers to the questions of what the NSK State should be like in the future and whether there is still a need for it. In fact, the sharing of information and free use of NSK iconography has always been vital for NSK; this has been one of its most important conceptual bases. The NSK citizens understood this point – and they have been using the NSK State in same spirit. (http://times.nskstate.com/outlook-words-from-africa-at-utopics/)

(for the NSK Citizen's Congress in Berlin Nov. 2010 see: http://congress.nskstate.com/)

The outline of the EAM offered a very clear structure of the project’s aims. What kind of (re-) presentation do you have in mind for the projects Words from Africa, Collection of Volk Art or the NSK Citizen’s Conference?

BV: There are a number of projects in which IRWIN has dealt with the state, its institutions, and its symbols. As a rule, it’s not only about a state, but the NSK State: a state that exists not in space, but in time, and that has been at the centre of many IRWIN projects over the last fifteen years. As a matter of fact, the NSK State exists exclusively via the various projects in which it appears; following one another in time they constitute a silhouette drawing, an outline delineating the image and the content of the NSK State.

When at the beginning of the last decade an Internet site appeared under the name nskstate.com that was not run by NSK or by the NSK State but by an NSK citizen, we were surprised that somebody was presenting, commenting and speaking in our name. Instead of denying him the right to do so, we established friendly relations with him and started to supply him with information. On the base of this hardly self-evident decision the site developed into the site of NSK citizens.

The next decisive moment appeared in 2007 when, mediated by nskstate.com, we started to get a big number of passport applications from Ibadan in Nigeria and it was obvious that it was not happening because of art.

In turn, the conference is a natural development of the process that was initiated by NSK, although but mainly occurring behind our backs. It is not about representation, but rather about construction and both projects NSK State in Time and EAM have this in common. It is about how these different processes, based on need, private initiative and chance, get formed into an entity, the NSK State in Time.

Throughout the entire term, three constitutive groups of NSK took the following positions in relation to their activities back in 1984: Laibach were politicians, Theatre of Scipion Nasica took the position of religion and IRWIN was a chronicler. So it is understandable that IRWIN is going to make a documentary about the congress.

While EAM has questioned the notion of a world divided in East and West, the political, social and economical situation has been crucially aggravated. In what way the following projects will react to the new situation?

BV: Are not difference and differentiation of major importance when art is in question? There are countless books written to define differences between very similar works sometimes. What we were confronted with at the time of political changes at the beginning of the 1990s were two parts of Europe that had been divided for 50 years. With all respect to numerous personal tragedies related to the period, we should admit the magnitude of the event, an experiment beyond all comparison. It was obvious from the beginning of the 1990s that the interest to bypass the difference was the political aim on both sides; however, what had already been eliminated was exactly the potential of differentiation. Instead of acknowledging the line of division in the centre of a newly united Europe and taking advantage of it, it was evacuated to the borders of it.

NSK passport holders had been closely related to the field of art until 2007 and although the reasons for possessing the passport differ according to the position and status of every particular passport holder, it is possible to maintain that the NSK passport is understood as an artifact which has, in certain cases and out of necessity, also been used for non-artistic purposes. Regarding the applications for the NSK passport from Nigeria, it has to be stated, that the cost of the passport is not high, but for the inhabitants of the so-called third world this is hardly unimportant. We seriously doubt that the interest of people from Nigeria in getting the NSK passport is related to art. It seems more likely that in the third world, NSK passports have ceased to be artifacts and have become useful documents. It is interesting how, on the other side of the protected borders, a symbolical object, that has been sold in the market of the first world for fifteen years and is recognised – regardless of its ambiguity or precisely because of that ambiguity – as an art object, has become a functional document in the third world. In short, it is interesting how the word has become flesh.

PDF Download Qucosa Publikationsserver

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa-69422

Veronika Darian (Leipzig/Berlin)

Theaterwissenschaftlerin, Assistentin am Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der Universität Leipzig, aktuell Vertretung der Juniorprofessur Tanzwissenschaft am Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin

Zusammenarbeit mit IRWIN bei dem Projekt: Mind the Map! – History Is Not Given

Publikationen:

Mind the Map! – History Is Not Given. A Critical Anthology Based on the Symposium, hrsg. v. Marina Gržinic, Günther Heeg und Veronika Darian, Revolver, 2006

Examining the Excavations of History: Veronika Darian on the Genesis of the "Mind the Map!" Project

http://times.nskstate.com/outlook-words-from-africa-at-utopics/