Nyota Inyoka, Biography, Archive

On the research project “Border-Dancing Across Time”[1]

Franz Anton Cramer in collaboration with Sandra Chatterjee

“And nothing starts in the Archive, nothing, ever at all,

though things certainly end up there.”

[Carolyn Steedman, Dust]

Introduction

The dancer, choreographer, author, and pedagogue Nyota Inyoka is at the center of a research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) for a period of four years, starting in June 2019.[2] One of the three research questions of the project[3] is related to the more traditional area of biography research. Nyota Inyoka (1896-1971), however, turns out to be a complex case of a life story suspended between fact, fiction, narrative legend-building and self-determination; it necessitates – at least for this research team – a new form of reconstructing a lived life. This biographical approach also requires a new approach to archives as a place for discovering relevant facts, a place of validation or falsification of hypotheses and assumptions.

What seems to distinguish Nyota Inyoka’s biography is that she never disclosed many details about her person, such as about her origins and family background. After three years of research the findings suggest that Inyoka worked in specific ways with culturally habitualized codes, that she in a way played with them, definitely however used them, in order to sculpt (one could even say in order to control) her persona not only in public (media and live), but also in her personal, private context.

The peculiar modernity of her way of life manifests itself in the transcontinental network of her lived experiences underlying the creation of her subjecthood, as supported by the archival evidence until the 1960s. This essay concentrates on initial biographical designs and tries to illuminate the dynamics of archival processes involved.

Fig. 1: Grave of Nyota Inyoka at the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Photographed November 2019. Photo private.

1) The Starting Point: Nyota Inyoka in the Canon of Dance History

Nyota Inyoka hardly found a place in the habitual canon of dance history. The few mentions of her are not precise, sweeping, and have been transmitted, as we found out in the course of our research, without any critical analysis of the sources [Golovlev 2019; Jahn 2016; Légeret-Manochhaya 2014; Suquet 2012; Décoret 1998; Robinson 1997/1990]. It is apparent that little historiographic attention has been paid to the artist, her work and her life.

Inyoka called herself “danseuse hindoue”, in other words ‘Indian’ dancer, or, more precisely, Hindu-dancer.[4] She thereby inserted herself into the context of the so-called ‘exotic’, which received broad and attentive reception especially in the time before WWII [cp. Décoret 1998; Cohen 2011; Coutelet 2014; Haitzinger 2016], but was hardly paid attention to post 1950. Understanding the reasons for this change in artistic reception of (assumed) extra-European dance forms, as hybrid as these might have been[5], and the ensuing neglect of the artists working in this field is part of this research project. The changes and break in colonial power structures, however, seem to be a decisive factor. The independence of India, first from the British Empire in 1947, then from French influence in 1956, and later the collapse of French, Belgian, British and also Dutch colonial power on the African continent since the late 1950s, as well as approximately a decade earlier in regions of Asia, left a mark on Nyota Inyoka’s artistic development. Post WWII, the emphasis of her creations focuses more and more on spiritual and universalist themes. It is our hypothesis that she did so in order to overcome the widespread geo-cultural assignments of her dance forms.

Her extensive oeuvre spans more than four decades; thus far it has not been comprehensively researched and recognized in its complexity.[6] This fact is even more surprising since the artist herself was present in multiple respects and can be regarded as socially successful in Paris, which was the center of her life.[7] She lived in a sophisticated Art Déco apartment building at the west end of Paris, in the distinguished 16th arrondissement. The list of people she corresponded with, as far as the research team has found out so far, includes illustrious personalities from different walks of life, especially, however, the persons from the cultural field, nobility and scholars.[8] However, at the time of her death in 1971, even though six daily newspapers announced her passing briefly,[9] the only comprehensive obituary we know of [Jacquinot 1971] appeared in an art magazine with limited circulation at the initiative of her family[10]. It appears as though the process of forgetting already begun in the 1960s.[11]

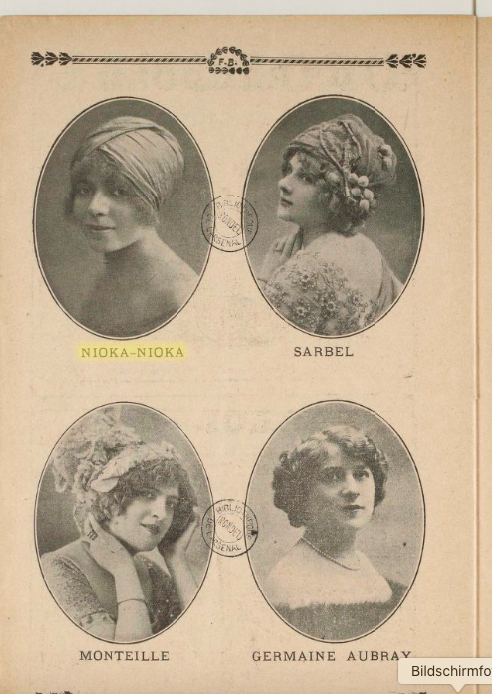

Fig. 2: Anonymous portrait of Nyota Inyoka from a program for

Revue féerique at Folies Bergère, 1917.

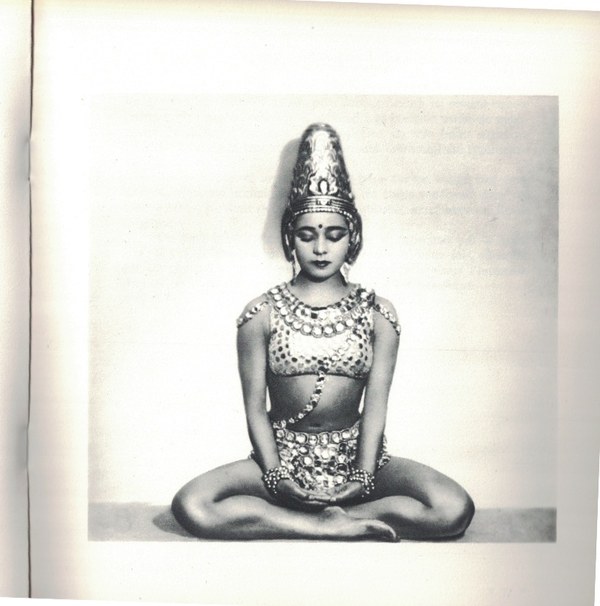

Fig. 3: Nyota Inyoka in her repertory piece Vishnu Rama, 1921;

from the monograph Nyota Inyoka by Loulou Roudanez, 1947.

2) Nyota Inyoka: Archival Processes

The quest to understand Nyota Inyoka’s life better has led us to a variety of archives, collections, databases, print publications, material evidence and contemporary witnesses. The material is still far from being comprehensively evaluated and interpreted, and the research continues. The historiographic process is incomplete and will remain so in the foreseeable future. Many details remain unclear and encourage making assumptions, which again, lead to new questions, sources, and repositories.

We are encountering obvious variances and accordances with respect to the accessible archival materials not only within our own team with its different perspectives but also in relation to the archive as an agent in itself. The aspect of archive as an entity that is not just available, but follows its own laws, regulations, histories, and atmospheres, that advances insights, slows them down or changes them, is gaining more and more attention in socio-historical research and shapes the project Border-Dancing, too. Already in 2001 Carolyn Steedman writes:

Fifteen years later the authors of The Archive Project – with reference to Steedman among others – ask very similar questions regarding the “archive-as-subject” and the “archival sensibilities” of researchers [Stanley 2017: 66]. They also deal with changeable conceptual approaches:

In this sense, historical research is highly dependent on collecting a specific corpus of source material. Tracking sources is on one hand an elemental part of the craft of historiography, particularly of biography research. On the other hand, the state of available sources is not only determined by the heuristic interests and the investigative skills of researchers, it is also significantly determined by the conditions of transmission and the genesis of particular collections. For this reason, Nicholas Dirks talks about the “Biography of an Archive” [Dirks 1993], and even its “Autobiography” [Dirks 2015]. Antoinette Burton looks at this aspect of the subjectivization, or the agency of the archive in terms of “Archive Stories” [Burton 2005].

2a) The Available Sources: Estate and Self Archiving

In the case of Nyota Inyoka we can draw on three corpus groups: (1) the estate, as it is safeguarded at the French National Library; this contains Inyoka’s (2) self-collected archive, understood here as an aggregate of her writings and notes, as well as images in the sense of a “fonds d’archives” [Sebillotte 2015]; and finally (3) materials in other collections and archives.

The estate contains voluminous self-archived documents of her professional activities, such as press dossiers, program notes, business correspondence, etc. Notably it contains a surprising wealth of artistic and publishing projects, which never, or only in a very limited way, found their way to the public.[12] This estate came under the care of the French National Library 13 years after Inyoka’s death and is today conserved in the department of performing arts under the call number COL 119.

Even as the fonds is very rich, it is unclear at this moment how complete the materials are, or rather, what could be the reasons for specific lacunae and gaps. For example, we do not know if a collection of books was part of the inheritance.[13] Also, no official or personal/identity records are part of this collection. At the same time, we can gather a lot of information from diaries and very personal notes, which arguably were never meant for the public. Had Inyoka consciously compiled what should be passed on while she was alive, these documents would probably not have been in the collection. Her inheritance, therefore, sheds light on the process of self-archiving. Especially at the intersection between documentary transmission and subjective processes of selection, essential questions regarding the original scope and motivations remain unanswered.

2b) Available Sources: Third-party Archiving

Nyota Inyoka was a much-noticed artist from the beginning of her career around 1920 until the end of WWII, as the large number of visual documentation within contemporaneous institutional collections as well as the large number of publications in the press about Inyoka, her performances, and her life attest to. The announcements, reviews, reports, and portraits can, on one hand, today be accessed via digital repositories. On the other hand, they are also part of important collections, such as the ones created by the Archives Internationales de la Danse (A.I.D.) starting in 1931.[14] Even the so-called Fonds Rondel, which is also the gamete of today’s department of performing arts of the French National Library, contains four comprehensive volumes about Nyota Inyoka, commonly called “recueils factices”[15]. For this press clippings, photographs, program notes or event announcements and images were chronologically pasted into scrapbooks or filed in folders. Fonds Rondel also provides cross references to other parts of the collection in which Inyoka appears. Often those are materials of other productions, in which Inyoka participated, such as in the dossier “Guillot de Saix”, whose “Indochina Idyl” Mademoiselle Libellule premiered in Cannes in 1932 and was restaged one year later in Paris under the direction of Nyota Inyoka. However, Inyoka also appears in other biographic fonds, such as that of Géo Sandry[16] or of the theater director Gaston Baty, as well as in the theater listings, under “Pré-Catelan” (one of the theatres which Paul Poiret managed in in the early 1920s) and “Théâtre du Montparnasse”.

Because Inyoka was in active exchange with many cultural practitioners of her time, letters are found in many collections pertaining to other people as well as (partial) estates, such as that of the association Art et Action (Louise Lara, Édouard Autant) or in the estates Gustave Fréjaville and Joséphin Pelladin.

However, Nyota Inyoka is not only present in French archives and collections and indeed extensively (which can be attributed to a wide reception of her work during her time, quite in contrast to her disappearance from public reception since the mid-1950s). Documents about and by her can be found in the New York Public Library – Performing Arts Division and at the Getty Center Los Angeles. The search for sources is not yet complete and will have to be continued in French as well as international LAMs[17]. When looking at the sources found so far and at their interrelatedness, however, it already emerges that the standing, reputation, and regard for Inyoka almost turned into the opposite in the second half of the 20th century.[18] Understanding the reasons for this change is a primary focus of the research project.

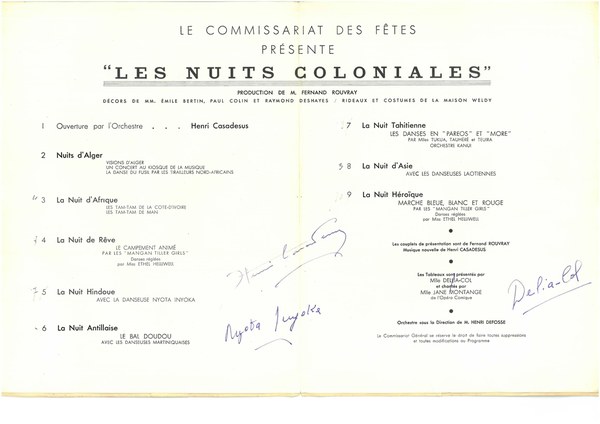

Fig. 4: Program note Nuits coloniales in the context of the Exposition coloniale internationale 1931 in Paris, with autographs by Nyota Inyoka, Henri Casadesus and Mademoiselle Délia-Col, private collection.

3) Archive Is Not the Same As Archive

This biographical research makes apparent how inadequate the hitherto used methods of dance historiography, focusing predominantly on the aesthetics of the choreographic work are in the case of an artist who has used specific, resistant, and self-determined modes of producing her biography. It clearly indicates that the autobiographical accounts have to be read in a larger context. An understanding of her artistic and intellectual oeuvre cannot solely be determined from the perspective of dance, choreography and performance practice.

If the hypothesis holds up that the archival and the biographic interface in Nyota Inyoka’s case in a specific way, not beyond but before her artistic work, it would have to be examined what notion of archive or concept of archive should be used. In any case, the paradigm of being coherent and self-contained stands next to constant reconfiguration, without being methodically mutually exclusive. In what follows, initial reflections will be articulated that aim at methodologically connecting the ‘archival’ and the ‘biographic’ in a way that shall facilitate biographical research to approximate a dynamic that matches the intrinsic incompleteness of the archive as a material space of knowledge and a hermeneutic cultural space.

The archive understood as a tool of historiographic work is presumed to be a more or less neutral space, which is visited by those who are in search of traces, sources and testimonials. In this respect the project Border-Dancing has thus far been highly successful and has paid heed to the dynamic interaction of sources of different provenance, through which the lack of information has been continually reduced by accumulating documents — also by way of coincidences and contingencies of searching, or rather: caused by the Agency of the Archive.[19]

There is, however, another, less positivistic point of view which Carolyn Steedman suggested already in 2001 while engaging with Derrida’s equally canonical and abstract notion of archive. Her reading of Jacques Derrida’s mythologized Archive Fever[20] leads her to insightful differentiations. Derrida is firstly concerned with the “moments of inception” and the search of “the beginning of things” [Steedman 2001: 3], in other words, “to find and possess all kinds of beginnings” [Steedman 2001: 5] as well as the connection between "speech and writing" [Steedman 2001: 6] as a specific collusion of (the recording of) history and its fabrication.

Secondly, however, she examines the concrete topology of the archive, its location and its materiality — aspects which usually are completely omitted in discussions of archive: “Commentators have found remarkably little to say about record offices, libraries and repositories, and have been brought face to face with the ordinariness, the unremarkable nature of archives.” [Steedman 2001: 9] But archives are always housed somewhere: in buildings, rooms, houses, boxes and cases. It is the “location of the Archive”, its material constitution. Nevertheless, the concreteness of the archive, its practice in the actual sense, is ignored in Archive Fever.

But the archive as a resource of historical research or at least research of historical events and persons is precisely not a space for the working of primarily male imaginary powers, but an organic and atmospheric ensemble, in which researchers have to integrate themselves. More than the reflections concerning theories of archive of the archival turn in the humanities in the last 30 years it is the performative aspects of archive that research practice has to engage with.

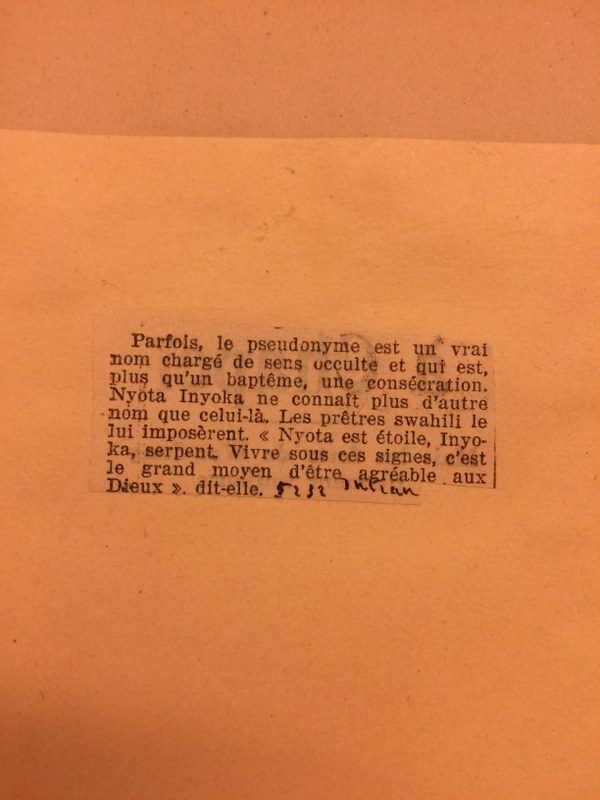

Fig. 5: Note in the newspaper L’Intransigeant, 5th February 1932: “Sometimes the pseudonym is a real name with a hidden meaning that is more than just a denomination, but a consecration: Nyota Inyoka does not know any other name than this just one any more. Suaheli priests have given it to her. ‚›Nyota‹ means star and ›Inyoka‹ serpent. She says, to live under such signs is the great means to live a life ‘pleasing to the gods’.”

4) Nyota Inyoka’s Biography as a Case Study for a New Archivality

With Derrida and adepts it is always only arkhons, in other words the patriciate of attic society, who control the archive and its explanatory power. It is a patriarchal notion of archive and archival practice; and not only that: it is also borrowed from a society in which – and Steedman points this out several times – the by far largest part of the population, namely slaves and women (not necessarily in this order) were excluded from being able to and worthy of being archived [cp. Steedman 2001: 38-41]. In contrast, modern archives, which have been instituted in Europe since the 19th century as national(ized) projects of knowledge and repositories of political affirmation, are more open, transparent, and easier to locate, indeed to access.

Generalizing texts about archives skip peculiarities and concrete power structures, in other words: the concrete conditions of transmission, which relate to the origin and interaction of sources, their storage and accessibility. It is precisely at this point that the social and historical conditions of the times come into play, which the grand archival narratives like to omit.[21]

From this perspective Nyota’s biography manifests itself in several ways: by way of her own writings; her professional standing, which is reflected in the archival and documentary collections; in the gaps in transmission, the scope and motives of which we do not know or know enough. The archival principle, however, manifests itself in a specific way also in the way she led her life and viewed herself, in the way in which she works, thinks, explains and creates.

At the same time, she refuses to abide by the classical biographical dispositifs by invoking visions, callings, inspirations from stars and cosmic powers, which had crucially opened up and shown her the decisive developments of her worldly existence.[22] In certain ways she undermines her own authorial position, which in other places she affirms and defends with vehemence.[23]

The Arkhontic, i.e. the (male) principle of the foundational and also of the disposition of world, ideas, and memories does not apply to her: she says ideas were not ‘hers’; by way of stubborn silence she does not give any space to her official identity (or too much room for the speculations of others in this regards, including researchers[24]), she ‘belongs to no one’ and while she has a life story that can be narrated, she does not have an origin. She possibly imagines her origins — we do not exactly know. In any case, she elegantly circumvents the Ur-power of the archive, even as we continue to search it in quest of facts about her father, for her name, her economic situation, her successes. It should not be forgotten, perhaps, that it was her niece who made the documents Inyoka left behind into archival material, and that it was later researchers who elevated these (now) archival materials into historical fact.

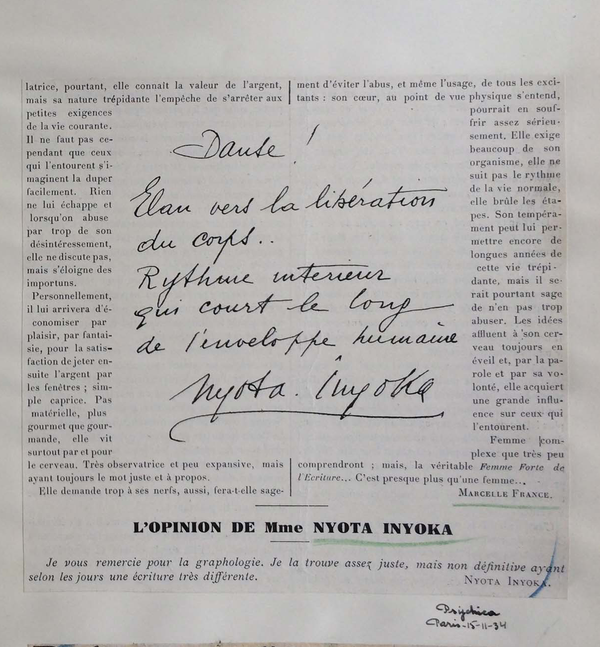

Fig. 6: Excerpt from an article in the magazine Psychica, 15th November 1934, containing the fac-simile record of a text by Nyota Inyoka: “Dance! Verve towards liberating the body … / Rhythm inside, flowing along the outer sheath of man. Nyota Inyoka”

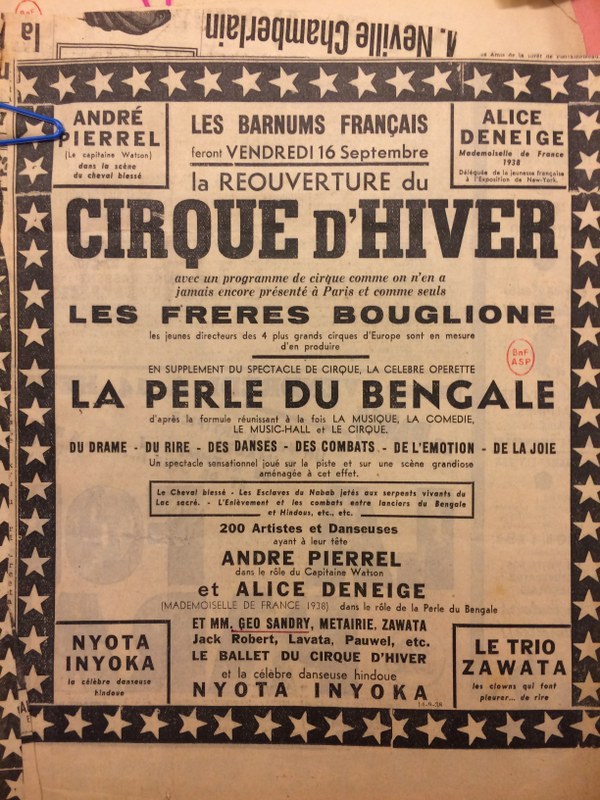

Fig. 7: Advertisement paper of the production La Perle du Bengale

at Cirque d’Hiver, 1935

5) A Complex Oeuvre

Inyoka's life is marked by questions of ethnicity and racist ascriptions[25], by enigmatic familial entanglements[26], a transnational lifestyle, spirituality, social upward mobility and, as it appears to us at this stage, a skillful self-positioning within increasingly fluid social and discursive dynamics. From the thus far analyzed documents of different kinds, a shining image of Inyoka’s artistic oeuvre emerges. It distinguishes itself by a large variety of forms of staging, by different degrees of authorship and also of media, in which her artistic position becomes visible, or which provide a frame for her work, respectively.

It has been reported unanimously that Inyoka’s debut occurred under the direction of the couturier Paul Poiret’s in spectacular revues at the Théâtre de l’Oasis in 1921-1923 [Robinson 1997; Suquet 2012]. In fact, however, the artist had already performed in 1917 at the Folies Bergère – at that time still under the name Nioka-Nioka. She was presented as “Perle d’Asie” as part of the Revue féerique in 26 tableaux and with “200 personnes en scène”, among them the Tiller Girls[27]. The earliest portraits of Inyoka which we have been able to locate, come from this context.

In the season 1920/21 — still before the productions with Paul Poiret at the Theaters de l’Oasis and du Pré-Catelan — Inyoka performed in the musical theater production L’Atlantide as an Egyptian dancer. This production adapted the popular novel by the respected writer Pierre Benoit, published in 1919 under the same title [Benoit 1919] for the stage. In the same year a silent film[28] based on the same sujet was released in movie theaters. What is significant for this sensational novel and its adaptations for stage and film[29] is the peculiar colonial fantasy that is articulated in it. Next to a male angst of a matriarchially ruled, archaic empire, the work also anticipates the historical development of the collapse of the colonial project: officers of the French army in Algeria fall prey to the charms of queen Antinea, whose kingdom in the Hoggar-mountains at the core of the region in North Africa under French colonial rule, Algeria, refers back to the legendary Atlantis. The novel connects this Tuareg dynasty to the last Egyptian queen Cleopatra as well as at the same time to the legacy of Carthage, whose flourishing culture was destroyed by the Roman colonial power in the third Punic war (149-146 B.C).[30] Thereby the novel implicitly thematizes subjugation of territories on the African continent by European powers in its historical continuity.[31] L’Atlantide thereby invokes a geographic, cultural, and political context which played a significant role in Nyota Inyoka’s life.

For in 1931 the International Colonial Exhibition took place in Paris, marking the beginning of a process which looked at the colonies no longer as a mere resource for the motherland, but instead developed a model of an expanded France — "La plus Grande France"[32] — in the sense of a developmental colonialism[33]. 1931 was a decisive year for Nyota Inyoka, because she was asked by Marshal Hubert Lyautey, its Commissary General to participate in the stage program and notably, to create a Gala performance about India. The reason behind this request was that Great Britain refused to participate in the exhibition; therefore, the primarily British colony India was underrepresented. Inyoka, who already had become known for her repertoire performances consisting of dances marked by a vague ‘Indianness’ based primarily on a staged embodiment of historical and iconographic traditions)[34], she now became a quasi-official representative of a culture which she invokes again and again in her life and biography – for example by way of asserting that she was born to an Indian father in Pondicherry, in the South East of the subcontinent.[35] Due to the success of this endeavor and the great resonance in the press Inyoka felt encouraged to start her own company: the Ballets Nyota Inyoka. This was a dance group that existed, in changing size, until the end of Inyoka’s stage career in 1957 and was largely composed of dancers with mixed heritage, most of them female. The debut of the company was in December 1932 at the avant-garde Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier, featuring a program of reconstructed cult dances attributed to India, Egypt, and Ethiopia. It ran several weeks and elicited a significant press resonance as well. This date definitely marks Inyoka’s arrival as an artist.

At the same time, Inyoka also strove to establish herself in high-art spaces. An exchange of letters with the director general of the Paris Opera, Jacques Rouché, document her proposal to realize a ballet about motifs of Krishna at Palais Garnier[36]. The project did not materialize, but Inyoka was hired in the performance season 1931/32 as a guest-dancer with an “exotic dance of Deïla” in the second act of a production at the Opéra-comique[37].

Nyota’s artistic success between 1920 and 1940 was sweeping, and led to her being chosen as the official representative of the Republic of France at New York’s 1939 World Fair. The New York Public Library houses correspondence between the organizers and Nyota Inyoka negotiating fees, travel expenses, etc.; the outbreak of WW II thwarted this prestigious plan.

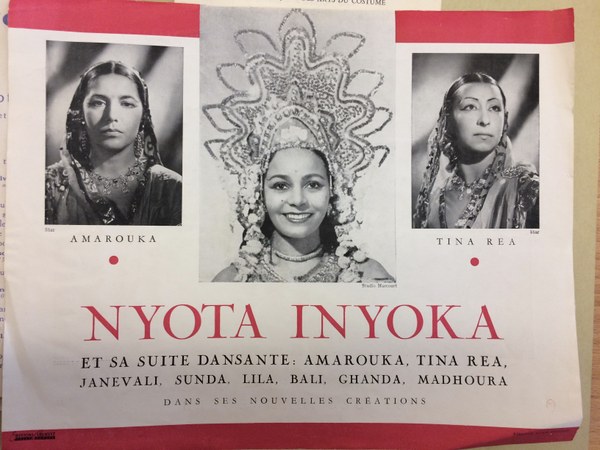

Fig. 8: Program note “Nyota Inyoka et sa suite dansante”, no date.

Conclusion

The narrative of Nyota Inyoka's life can and will be continued. Her life in the years post 1945 are as rich in terms of biographical changes and open questions. But it is bound to confirm the specific relation between life materialized as a public one and identity constructed as idiosyncratic or even hidden. This specific context is required in the research process which intends to understand biography as archive and use it accordingly – as material of a cumulative process at the preliminary end of which there is a historiographic artifice whose validity has to remain bound by time as much as the lived reality of the artist in question. Just facts – let alone just names –are not enough to reconstruct a life, which on one hand produces its own complexity and on the other is also assigned complexity based on the social and libidinous circumstances of her time. In the end it is about understanding in how far the persona, the figure, and the identity of Nyota Inyoka are constructed and ‘produced’ as much as they mark a coherence in the constant strive to control one’s image to the outside, and to work on oneself.

Steedman points out that while the biographical and the historical are connected, they operate following opposing parameters:

This juxtaposition of anthropomorphic and narrative approaches or perspectives is decisive for history, but also for the claim for totality of one's own narrative, because history has no end, but biography does — in death:

Nyota Inyoka therefore undermines the supposed power of the archive. She strengthens its performative aspects, the temporary and ephemeral. In fact, she did not even create an archive herself but appeared primarily as a subject of archival research and practice. Thereby she simultaneously alienates and affirms historiography as practice. For all historic activity, all historiographic narrative are essentially provisional: “Historians are telling the only story that has no end.” [Steedman 2001: 148]

These life historical stories do not necessarily go back to archives. However, the biography of Nyota Inyoka is not graspable without the archive. That is where her paradox can be located. Because the male dominated concept of archive, as Derrida describes it and as it accompanies the archival turn, she nonchalantly diverts it. Even though her artistic ‘originality’ is attested again and again, she herself repeats tried and tested formulas and invokes higher powers instead of her own genius. One could say she does not actually need an archive; only those who want to build a biography from records need an archive. But for this they are missing crucial documents, or more generally speaking documentary material and robust sources. What the sources state is affirmative, not conclusive or even investigative. They only affirm what we already know and what Nyota decided to let the world know. The ‘actual’, the ultimate source is missing. Maybe if we found more witnesses and testimonies, and could sift through more electronic repositories and analyze even more remote archival materials, maybe then the desired facts, the intimate truths would come to light. But the truth belongs to Inyoka; she bartered it with Clio the Muse of History in return for her silence[38]. When we try to reconstruct the life story of Nyota Inyoka, we depend less on the diffuse power of archives and more on the concrete control this artist exerted over her appearance in this world – an end, no closure. Or the other way around.