Envisioning Future Bodies: Choy Ka Fai’s experimental practice at the interface of choreography, media art and archival processes

Choy Ka Fai (Berlin) in conversation with Lucie Ortmann (Essen)

“Only dance is capable of creating a body of the future,”[1] the Berlin-based Singaporean artist Choy Ka Fai has said. His work in stage, exhibition, and digital formats, often shown in combination[2], brings living and dead people into contact with virtual beings, and interweaves historical, contemporary and fictional material. For over ten years, Choy Ka Fai has experimented with documenting and making dance accessible, via a multimedia practice that operates at the interface of choreography, media art, and archival processes. Exploring the relationship between artistic expression and digital technology, he creates pieces such as Prospectus For a Future Body (2011), in which he used digital technology to chart, store, and reproduce a body’s movements. He researches the possibility of learning choreographies through externally controlled movement impulses and incorporates playful, humorous or self-reflective elements and commentaries into his works, appearing himself as a moderator, curator or host. In Dance Clinic (2017), for instance, Choy appeared as a “dance doctor” aiming to improve or “heal” choreographies and dancers’ performances with artificial intelligence.

Pictures 1+2: Performance of “Dance Clinic” at tanzhaus nrw, Düsseldorf, photos: Katja Illner

His generally multi-part, long-term projects are based on intensive research and a growing fund of both acquired and specially generated documentary and fictional material. For SoftMachine (2012-2015), Choy Ka Fai interviewed choreographers, dancers and curators from China, Japan, India, Indonesia and Singapore about their work and developments on their local dance scenes over the past ten years, and created performances in which four of these dance artists showed their versions and visions of contemporary dance live. Devised as a multimedia archive and performance cycle, SoftMachine arose from a desire to break down clichéd and exoticizing notions of “Asian dance” by presenting a wide range of artistic positions and unique practices. In his 2015 presentation of the project in four rooms of Weltmuseum Wien as part of the ImPulsTanz festival, he incorporated photos and objects from the museum’s own holdings.[3]

Pictures 3-6: Exhibition views of “SoftMachine: Exhibition” at Weltmuseum Wien as part of the festival ImPulsTanz 2015, July 26th to August 16th 2015, photos: Simon Kaefer

Questions concerning the futuristic and queer potential of human and digital bodies are central to Choy’s work. Dubbed a “speculative designer”,[4] he is interested in the human body as a tool for exploring spiritual experiences and the intangible potential generated by multimedia experiences. He combines new technologies with traditional rituals, and states of spirituality with speculation about the posthuman body.[5] In UnBearable Darkness (2018), about the Butoh artist Tatsumi Hijikata, Choy Ka Fai asked “what is humanly impossible and ghostly possible”[6] and conducted a séance to interview the spirit of the late Hijikata through a shamanic medium. The piece culminates in several avatars of Hijikata, representing the artist’s different creative phases and ages, dancing with each other simultaneously.

Pictures 7-10: Choy Ka Fai “UnBearable Darkness”, digital images (7+8) by Choy Ka Fai, performance photos: Katja Illner

Trailer “UnBearable Darkness”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7WH3pKYnbI

For the research project CosmicWander (2019-ongoing)[7], Choy travelled to various Asian countries to explore and document a range of individuals’ and communities’ spiritual practices and dance cultures. The presentations that emerge from this project are part lecture, part performance. They show live hook-ups with performers in different locations around the world, archive material, and avatars that are created and moved live. The technical parameters are deliberately exposed while certain material and atmospheric elements cite spiritual rituals: burning incense sticks fill the venue with a distinctive smell and audience members are served aromatic ginger drinks.

In the following interview, conducted via Zoom on 2 February 2022, Choy Ka Fai stresses the key importance of the practice of archiving for his work. He talks about the methods he uses to show, share, and further develop the material he has extensively collected and generated in ever new formats, ranging from performance, video installation, and lecture to digital games. He also reflects on the challenging processes of transferring and translating spiritual practices and dance cultures into different contexts and for different audiences.

Lucie Ortmann: How did you start archiving by different technological means (video, digital tools like motion capture) as part of your work? Was it always your aim or did it happen intuitively during the creative process, expanding organically step by step?

Choy Ka Fai: I think it began for a few different reasons. I originally trained as a video artist. My first job after graduation was as a documentary maker and collaborator for the Singaporean theatre director Ong Keng Sen. I got a close look at how he made docu-drama performances. That was inspiring and I learned a lot. Video became a very powerful tool for my experimentation. Somehow, I stayed in that comfort zone of video as a medium for researching, experimenting and creating. I worked on a project for Keng Sen in 2006, travelling with him non-stop for nine months and filming five different artist portraits for the performance. Afterwards I suffered from visual fatigue, I was unable to film anything, I lost my sense of the meaning in creating visual images. It took about 18 months before I could engage with my camera again. It was during this period that I started looking beyond 2-dimensional video forms into 3-dimensional digital forms. This period coincided with my studies at the Royal College of Art and Design in London in 2009. There I was introduced to concepts of speculative design and the world of emerging technologies, for example fields of Synthetic Biology. It was also in London where I started the project SoftMachine, inspired by the curation and marketing strategies of Sadler’s Wells on dance in Asia.

LO: You have mentioned the impact of an exoticizing promotional video for their programme Out of Asia – The future of Contemporary Dance.

CKF: Yes, I thought to myself, if you do a festival about dance in Asia, it should not just include Akram Khan and all those big names – mostly European artists with Asian origins. So, I took my camera again and I travelled through Japan, China, Indonesia, India und Singapore – and consciously not only to the capital cities, but also to the other dance scenes around the country, and in the end I visited 13 cities in total. The camera became my device for understanding and accumulating dance knowledge. I became quite obsessive about documenting. I met and interviewed 84 dance makers and later on, SoftMachine expanded into a series of biographical documentaries and performances with four dance makers. At that time, I was influenced by the works of Jérôme Bel. I saw Pichet Klunchun and Myself many times and it inspired me a lot. It was initiated for the Bangkok Fringe Festival by Tang Fu Kuen, who works as my dramaturg, he guides me and provides context. So, instead of a European coming to Asia, I became an Asian going back to Asia. This whole series went on tour and there is very little technology. It was composed of simple, very intimate portraits of dance makers in Asia, but it is also about how I was introduced to the local contemporary dance scene in these countries. For SoftMachine I interviewed human choreographers; CosmicWander is a sequel to that, because instead of interviewing humans I wanted to interview spiritual presences. Above all I was fascinated by this very mobile motion capture kit. I could document a shaman with it, and thus possibly even capture the presence of a dancing god.

Trailer Choy Ka Fai “Yishun is Burning” https://vimeo.com/639009298

LO: For your piece UnBearable Darkness you kind of “resurrect” the dead Butoh artist Tatsumi Hijikata by both shamanistic methods and digital technology. Was this piece the first edition of your long-term project CosmicWander?

CKF: Not really. Unbearable Darkness was more paranormal. There is a funny story behind it. It started with an invitation from Gwangju Asia Cultural Center in Korea to make a proposal for their programme focusing on the Butoh Master Tatsumi Hijikata. My proposal was rejected and I console myself that it was too radical for them at the time. However, I had become so curious while researching that I decided to do it myself. It was the first time I met and spoke to the spirit of Tatsumi Hijikata through a Japanese shaman; it was a very intense experience as I was convinced it was him. Before I started CosmicWander, I was paying too much respect to the otherness. But when I entered the world of shamans, I realized they are much more progressive, much more open-minded. Nothing is wrong in their eyes.

LO: It seems to me UnBearable darkness has a rather closed dramaturgy; the research is integrated into a piece with a concentrated story-line – whereas the different editions of CosmicWander are more open, switching between lecture and show. You as the initiator, choreographer and technician appear on stage, artists from other time zones are invited via video calls. Seeing the same show months later for the second time in another city, I realized that you adapt it, change it, that it differs from place to place.

CKF: I think fundamentally there are two differences between UnBearable darkness and CosmicWander. For the Hijikata project, I collaborated with his official archive at Keio University Tokyo. I had a different sense of responsibility towards his legacy and at the same time it was very much my own voice in it. I think many people don’t know that it is not real at certain parts, it is a fantasy, a fiction. To dance with a ghost is a fantasy. When we first did a showing in Yokohama, I felt the working process was so fun and light! But for the premiere at tanzhaus nrw in Düsseldorf, it occurred to me that I had to contextualize all this material. I needed to renegotiate this question which I face all the time, because I always work with the dance of others: how do you talk about Butoh in the European world? In Japan, there are many things I don’t need to explain, I assume that people have some background knowledge; even the idea of a séance, speaking to a ghost, is taken as understood in many parts of Asia. But in Europe I must take extra care in terms of dramaturgy or translation. During our tour over two years before COVID started, I constantly re-phrased this interview with Hijikata to make it accessible to more and more people. At first, we were really trying to capture the essence of how the ghost speaks or the shamans speak in streams of thought, but outside Asia, I realized, people would not understand the nuances of it. By the time we went back to Kyoto a year later, I felt that it was an accessible text that anyone could approach. This was a challenge. Also, because I am a fan of Hijikata, I had to be extra-careful with representations. In this sense, yes, it is in a way cagey, a bit muted, I did a lot of conceptually outrageous things. Like the scene with the golden penis, I multiplied into a thousand penises, and I felt that when I showed it at ImPulsTanz in Vienna, all the Asian or Japanese audience members got the humor, but the rest of the audience took it too seriously. Hijikata is a very eccentric and playful artist himself, but I realized that this playfulness became muted in the Western world when I presented it. When I crossed over to the light – away from the ghosts and underworld – working on Yishun is burning, the first edition of CosmicWander, it liberated me. Back in Singapore I found a shaman who really liberated my mind. He showed me: It is ok, no cultural police is going to censor your work, I can express myself freely.

When you first saw Yishun is burning at tanzhaus nrw it was programmed together with a lecture. My lecture tells of me visiting a Chinese Jesus in Taiwan. For the non-professional audience, this, too, could be overwhelming, these images could seem almost like Asian Baroque. So, afterwards I kept on working, took the time to adjust all the translation, subtitling and the coloring to the version you saw six months later at Tanzplattform in Berlin. It was the same with Postcolonial Spirits: after the premiere at Tanz im August in Berlin, we spent six months making the communication process more accessible. I am bringing cultures into another realm or presenting them on stage as a kind of theatre. It is difficult to consider and convey the nuances and make the context of it universally accessible.

At the CosmicWander exhibition at Tanz im August, apart from the main installation work, I also presented a research archive on five different shamanic cultures. I saw that people were interested and could relate with it. Outside the theatre, in an exhibition context, you can take more time to look at the material than in these approx. 60 minutes of the show, where everything needs to be much more precise.

Pictures 11-16: Installation views of “CosmicWander: Expedition” at KINDL a spart of the festival Tanz im August in Berlin 2021, photos: Dajana Lother

LO: Do you like the idea of having a physical place for all your material and projects? Have you considered setting up an archive or a museum or something like that?

CKF: Yes, it is a dream, but it is very far away. I already sell works to museums or art spaces, but nobody buys SoftMachine, they argue that it is a dance archive, so it is for dance institutions. I recently found out how Tino Sehgal does it with his performative works: The main work becomes the instructions for the performance, how to restage the piece. I also face problems like that when making contracts with my dancers now, and we still don’t have proper answers. I motion capture these dancers, so when I give them instructions or show them a shaman and say please combine these three elements and make a dance for me: do I then have the rights to this motion capture? Or do the dancers who interpret my instructions own rights as well? I have a digital file of the dancer – it gets very complicated. With the new Siberian edition of CosmicWander, we have a shaman dancing in the VR and we thought we had better buy the rights on this motion capture, because if not, every time I show it in different contexts, I have to pay the dancer. Somehow, she is forever digitally performing in my piece.

LO: How would you like your multi-media archives to be used, what effect would you like them to have? Is the archive a working method for you, a tool of analysis and critical resource?

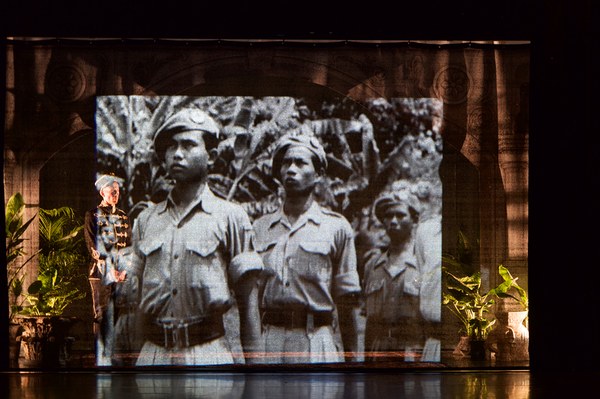

CKF: The notion of archiving is always present in my work. That is also why it takes so long for me to make a new work. The Indonesian piece Postcolonial Spirits[8] is a good case in point to answer your question. The dance I researched there is called Dolalak, which is not traditional, it only started in the 1930s. It is a hybrid of Dutch soldiers drinking and partying and traces of Javanese gestures and dance, together with Muslim poetry from Islamic culture. It is beyond the syncretic, it is more than syncretic, it is an amalgamation of so many realities. In Postcolonial Spirits the performance itself becomes the archive. I invited the Dutch performer Vincent Riebeek to relearn that dance given to the Indonesians, or somehow transmitted by accident by his forefathers, by the Dutch colonial soldiers in Indonesia. He is learning it from this young 21-year-old boy from the village where the dance developed. I have a kind of romantic idea of a conceptual loop, of transmitting this dance back into a Dutch body – that is the thinking behind making the show. I only went there once to conduct research; the documentation was made in February 2020 and Vincent has never been there. He learned Dolalak through the documentation and doesn’t do it perfectly. But that artifact or “noise” arising from his kind of inaccuracy is what makes the beauty of the show. We filmed the Indonesian boy with motion capture, to have a visual document. Thanks to this motion capture we have accurate records, but in the show, it is used to convey this idea of a romantic duet, a transnational, transdata duet on stage. If we want to keep the essence of that dance culture, we have it as a 3-dimensional archive, we have these documents, the motion capture, the costumes. I am lucky to be able to collaborate with musicians in terms of the musicality of it. The composer Yennu Ariendra is also researching trance and took the song from my field recording, so it is a little bit like anthropological work. We filed the lyrics and in one song we even experimented with singing it in English with Javanese intonations. Some naughtiness is there, because women were not originally allowed to sing the song. The opening of the ritual is sung by a low deep male voice. But at the end of the day, we are not anthropologists; we are artists and I am working with progressive artists as well. So, we are also participating in evolving the tradition of Dolalak.

Pictures 17-24: Choy Ka Fai “Postcolonial Spirits”, digital image (17) by Brandon Tay and Choy Ka Fai, photos 18-20: Dieter Hartwig, photos 21-24: Eddie Haryanto

LO: I feel like after seeing some editions and pieces of CosmicWander, I have more knowledge, which also helps to read the other shows. I feel this is important for the whole project, not only to enjoy, but also to understand or get to know more about those practices. Not only that, your research and network of local people seems to work against colonial, consumerist attitudes towards other cultures and their practices.

CosmicWander also deals with the possibility of translating live performances into a documentation or mediatized form. Was the idea of bringing together performers from different time zones and places a compromise induced by the pandemic, costs or environmental issues? I realized that your collaborators in different parts of the world must perform at between 2 and 5 in the morning…

CKF: That has a slightly capitalist edge. The money comes from Germany, so they must be there for the German performance time. But it is better than nothing for them because they have also been badly hit by COVID.

The first thing I learned was this idea in Eastern philosophy of taking care of your body by eating only until you are 70 percent full, exercising only to 70 percent of your capacity. I adopt this when I use the avatar. You could do 200 percent more with this avatar, but somehow, I leave it to 70 percent, I don’t do it to the maximum, because then its condition would become quite unstable. The use of only 70 percent of the energy makes everything smoother, including the transfer from the live body to the avatar. When you generate 100 percent energy, the computer has no way of determining it. It is one and zero, so they cannot give you this vibration of the 100. So, in a very Eastern way, the energy in my shows is always kept at a certain level.

Performing in different time zones and spaces was part necessity and we experimented a lot. At first, the dancers simply couldn’t come abroad. But then I also realized, when the musicians perform live, the avatar feels very cold. There is not enough warmth in the avatar. That was the initial reason why I invited the Singapore voguers to join. The main dancer performs via motion capture in a small studio in Bangkok and then I have three local voguers to dance on stage. The best scenario would be to have all of them, dancers and musicians, on site. But when we performed at tanzhaus in Düsseldorf, the musicians couldn’t come either. We needed to use the video as a medium, which I am familiar with, to convey their presence. Then there is the timing and the editing, these little things, the mastering of the sound to avoid the feeling of a studio-based album, to deal with. Errors also occur, which are purposefully left in, to create the feeling that it is live.

LO: The difference between the physical performances and the digitized versions is especially obvious when it comes to trance and ecstatic shamanistic dances. Alongside the digital technology and live performers, you also make use of material and sensory elements from spiritual rituals in your pieces – like burning incense sticks to create special atmospheres and address the audience’s senses. Through the different media, they are very much drawn in to the events, to the rituals. It makes me think about voyeurism a lot.

CKF: That is a very interesting point. I think this whole question revolves around the notion of different understandings of sacredness in different cultures. I think in general that people who are not familiar with the culture think: It is so sacred, I should keep my distance. But if you know it, it is not so serious and sacred. It is more about coming together, about the community gathering. Part of this Indonesian traditional dance, the Javanese dance, is that the performers invite the audience to join in, it is very sensual and more a social than a religious event. So, in the last show in Düsseldorf just a few days ago we did what we had wanted to do in Tanz im August, but couldn’t due to COVID: we let the audience come on stage. For me it feels like the proper way of ending. We try to transmit this folk dance through a Dutch body and then the music lingers in the space and the audience is invited to dance – which is what Indonesian folk dancers would do, dance together with the audience at the end. If you think this tradition of folk dance in parallel with spiritual practices, it is about believers or non-believers gathering, and it is also a spectacle, it is theatrical in a certain way.

LO: Still, especially in the case of Postcolonial Spirits I feel it would be wrong to jump up and dance a (post-)colonial dance. It raises problematic or difficult issues about appropriation and heritage.

CKF: But the main concern here is to highlight this evolution. I integrated a film of Balinese dance, of Instagram girls doing the Dolalak, into my research in 2020. And this is my interpretation: The world of TikTok and Instagram collides with the idea of pop culture consumption. Why shouldn’t the Dolalak come from the folk tradition to popular consumption? I feel it is ok, the move, the vibration, it is the same with pop music. For me it creates a beautiful mixture. At the end of our show in Düsseldorf, young street dancers came on stage and an old lady – and it was good because you don’t have to move like the Javanese. I think the most interesting feedback I got from the last show was that an audience member started to feel empathy towards the virtual character of the Dolalak avatar. Normally, you feel kinesthetic empathy to the live performer. It is a long show, and you travel through time and space to see this dancer shift from 2D to 3D and start to feel empathy towards him. That made me feel I had somehow succeeded.

As an immigrant, as someone bringing all this different culture to Germany, I feel protected in cities like Berlin or Düsseldorf, at institutions like tanzhaus nrw, because they are the ones that give me the chance to develop and show my work. But if you look at the dance scene in general, not many are interested in this stuff. After Tanzplattform, after meeting and talking to people and seeing other shows, two things struck me. The first was the question of whether my pieces are like sightseeing tours for the audience, a voyeuristic experience. I always self-reflect a lot in that sense. And the second thing was that the other works seemed quite empty to me. Academically, the Europeans or Caucasians have an upward vibration but Asian dance is always going to the ground, from two dimensions to three dimensions. Coming from my work with all these shamans, calling them vibration, I feel they are heading for some destination, they have some grounding. What is the point of showing that here? Is anyone interested beyond the academics? How do I communicate with the others? How can I communicate with the audience, with this type of vibration? My curiosity drives me to constantly research the unknown to me.

LO: They are very interesting points. Let’s come back to digitizing, because I think even beyond the pandemic it remains an important tool for bringing together and mixing people from the past and the present, spirits, ghosts and the dead. You use it to develop your own cosmos, in a sense, which you have called a digital metaverse.

https://blueskyacademy.digital/

The Blue Sky Academy, part of the “CosmicWander” series, combining dance, lectures, video screenings and a ‘tele-presence’ performance opens a discursive space that makes visible the shamans’ old, supposedly irrational belief system and alternative philosophy.

CKF: Digital worlds can be quite scary; they progress in the blink of an eye. When I finished the Hijikata project, UnBearable darkness, in 2018, I wanted to re-create Hijikata’s voice, because I have a CD from his funeral, from a private collection, where we hear his voice, and theoretically in English I could input his voice like they did with Obama. They put Obama’s voice through an AI program so you could tell “Obama” to say what you want. I wanted to do that for Hijikata, but there was no Japanese version. But I am sure you could do it today. The technology advances so fast. At the beginning of this year, I did the Vietnamese edition of CosmicWander. I started to work with the avatar’s voice. It is so simple; an I-phone connected to a gaming software by which I can animate my avatar talking or singing a song. The avatar I am developing in the new piece is based on Hồ Chí Minh, the former Prime Minister of Vietnam. I could make “Hồ Chí Minh” do a B-Boy-Dance or perform a rap and then talk with the same voice. So, you see how frighteningly fast the technology develops. With this project I am kind of trying to keep up with the technology. I have this fascination for having Hồ Chí Minh as a metaphoric avatar to tell the story of the Vietnamese diaspora in Germany. So, if I made UnBearable darkness today you would see an uncannier, i.e., more realistic Hijikata. And if I had double or triple the budget, I could use the hologram technology they use for those Japanese virtual idols. But I didn’t have the budget to do a hologram in a 3D space. The gaming industry, which I am also researching, is miles ahead. I have written a few proposals incorporating the field, but without success. People in the arts or dance can’t grasp what I am talking about. My proposal since the start of COVID was to look at gaming as a dance experience and how we use gaming or enhance the gaming technology in the art context. But so far, I don’t have believers willing to give me the support or confidence to make the work. The technology I used for my gaming projects is mostly free. You just need to know how to do it. But to produce a game you need a lot of resources. So far, I have only been able to make demos, taking a DIY, very independent approach, to create some scenes that can be played or allow interaction with the audience.

LO: Is the idea to also train the audience to dance, to involve them in a physical action?

CKF: The first step is quite deep and complex. From 2017 on I had this project called Dance Clinic. I was trying to devise an AI programme to understand or generate dance movements based on different iconic dances. The first thing is to build this thing called a stick machine. Because if you play a game, the interaction with the audience will make your character do different things. You could have a battle between Hijikata and Mary Wigman, a controller could make Mary Wigman dance, the Witch Dance or something, and we check how the AI would then responds. I want to develop this further, perhaps do a dance battle between Nijinsky and Hijikata, but that might be too outrageous. But I would like two players to have a dance battle across different time zones and across history. I have all these digital data, collected over the years in 3D form. I am always thinking about how I can put this archive to use. This game could be a perfect thing to do.

LO: It sounds exciting. Maybe you could also produce a new figure combining “templates”. I think the game could be an interesting new step for the CosmicWander project. I wonder if your research will ever be complete. Finishing the project will certainly be very time consuming!

CKF: Due to the pandemic, I haven’t managed to research the last part of CosmicWander yet. It is about the North Korean shamans in China. At the border of China and North Korea there is a Korean autonomous zone called Yanbian where there is a shaman village. I was supposed to go in March 2020, but even now it is difficult to travel there. I still hope to do it, because this North Korean or Manchurian practice is a link to all the other cultures I have researched. When I started, I was fascinated by the Cham dance in Bhutan as well – so I would be glad to continue it if I find willing supporters, if the conditions are right, if we can travel. I am also thinking of producing four films about the decade 2012 to 2022 with the material from the SoftMachine-project and all the interviews with the four dance artists. One of those I interviewed was the Japanese artist Yuya Tsukahara of Contact Gonzo. In our film documentary, we speculated that by 2022 he will be festival director in Kyoto, and it came true: he is now one of the artistic directors of Kyoto Experiment!

I have started to realize there is no end to any of my projects. It might seem like an end when I need to submit a report to someone or other. But then my curiosity just continues.

LO: Thank you for sharing your thoughts and your time.

Translation: Charlotte Kreutzmüller