Assembling a Work of Art: An Annotated History of Fluxfilm No. 1

Hanna Hölling (London / Zürich)

The Birth of Slowness

Anton came into the world in April 2020, during the global pandemic crisis. His arrival slowed things down for me. It was a deacceleration intensified by the lockdown of social and economic life imposed by the pandemic. The sudden slowness forced me to recalibrate my attitude toward work, life, and the world. Studying Anton’s face and the details of his body filled my days; I was immersed in the observation of his changing facial expressions, hopeful smiles and eternal disappointments in a sustained process of trial and error to that I could make everything right for him. This newly learned slowness has influenced the way I look at other things, bringing a tenderness with fresh possibilities, a fondness that in this new life constellation must be learned and navigated. This new state of mind and body has forced me to write differently, in a way that takes into account unfolding implications and that is honest about its source. It emerges from a burning desire to deeply immerse myself in and understand the problem at hand. It also arises from a wish to be effective without the impulse to force my object of study into the nearest available logic.

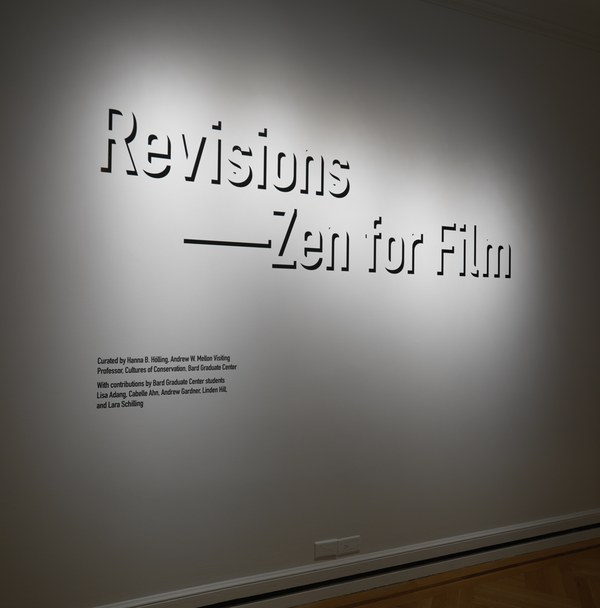

Already a work of slowness, Revisions: Zen for Film, revised again in the following pages, is predestined to be an exercise in slow looking. In its original form, Revisions combined a research project, pedagogy, an exhibition, and an exhibition catalogue.[1] Revisions wove facts and fictions into a coherent argument that attempted to explicate Zen for Film, one of the most well-known Fluxus films by the Korean American artist Nam June Paik, and, unsurprisingly, one of the most misinterpreted among his works. Faced with a conceptually and materially complex work, Revisions took the approach of surveying the many manifestations of Zen for Film, providing a framework for fully appreciating it. Without being deterred by Zen for Film’s complexity, Revisions engaged in a detailed narrative of what the work is as a matter of principle, without rushing into judgments or comfortable interpretation that might not cohere. But the work of art also had to be worth it and Zen for Film was certainly such a work—one that embodies the artwork’s struggle with identity and containment. At times, Zen for Film might not appear to be a work at all but rather an absence of it.

Image 1. Revisions: Zen for Film. Exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York, September 18, 2015–February 21, 2016. Photograph by Bruce M. White.

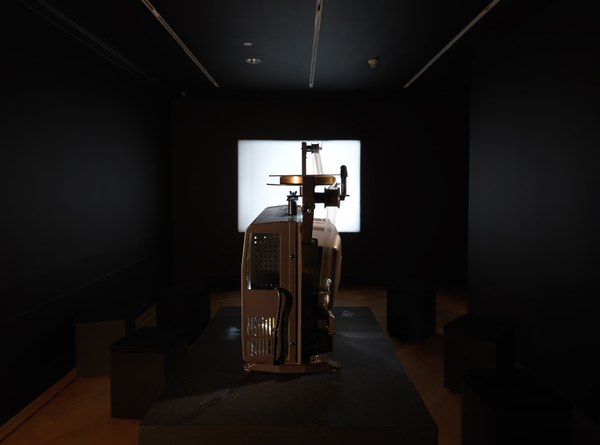

Image 2. Revisions: Zen for Film. Exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York, September 18, 2015–February 21, 2016. Installation detail: Zen for Film projection. Photograph by Bruce M. White.

In the following discussion, I will first recall what Zen for Film became during my yearlong investigation—an object, event, and a performance—with many facets, manifestations, and modulations. Along with three reprinted sections from the original book, I have also added new information generated in the course of loan acquisitions and mounting the exhibition in a renewed consideration of the work that approaches it as an ongoing process of assembling, performed by human and nonhuman subjects. The following sections question the ambition of constructing the work (that is, exhibiting and preserving it) with a fixed identity, a product that moves seamlessly from the studio to the world of dissemination, distribution, and display. Instead, Zen for Film will appear once again as an assemblage of people, things, and events, a vibrant materiality destined for a changeable future.

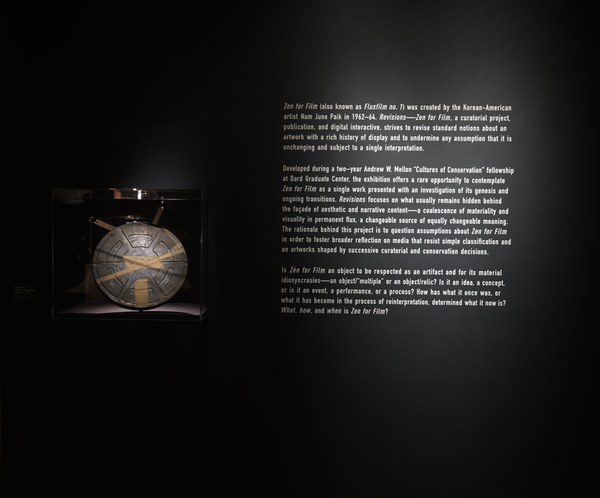

Image 3. Revisions: Zen for Film. Exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York, September 18, 2015–February 21, 2016. Installation detail: filmic relic from the MoMA Fluxus Silverman collection. Photograph by Bruce M. White.

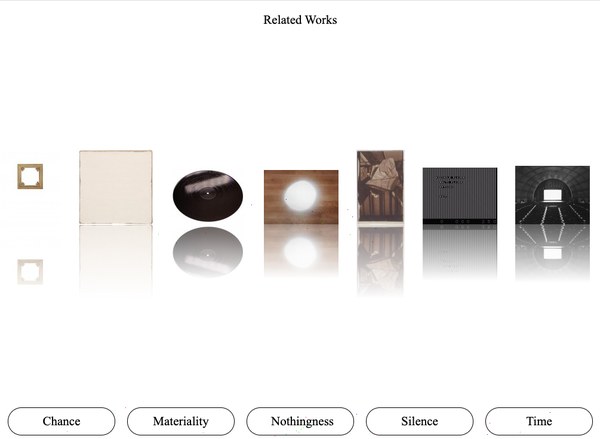

Image 4. Revisions: Zen for Film. Exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery,

New York, September 18, 2015–February 21, 2016. Installation detail: Fluxus edition from the MoMA Fluxus Silverman collection. Photograph by Bruce M. White.

What Is Zen for Film?

“What is Zen for Film?,” I was asked sometime in the early fall of 2014, on the occasion of a preparatory meeting for Revisions, an exhibition to feature Zen for Film (1962–64), Nam June Paik’s “blank” film projection. Despite the many discussions that preceded the meeting, when it came to the question of what the main—and the only—artwork of this exhibition was, we felt as if we’d been left in the dark. Curatorial engagements are not always simple. Only sometimes might they involve the pleasing task of assembling exhibitions from objects that tell fascinating stories. But the act of exhibiting may also fill the space with the vastness of a philosophical challenge, as in the case of Zen for Film. The gesture of exposing an artwork to the gaze of the viewer can pose arduous questions—questions with which one struggles without any hope of enlightenment and to which answers are always partial and imperfect. What, then, is Zen for Film? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to someone else, to paraphrase Saint Augustine, I do not know. Is Zen for Film an object to be respected as an artifact and for its material idiosyncrasies—an object/“multiple” or an object/relic? Is it an idea, a concept— or rather, an event, a performance, or a process? How has what it is been determined by what it once was—or what it has become in the process of reinterpretation? How has it been affected by conceptual and physical change? All in all, what, how, and when is the artwork?

Featuring the film as its main character, the exhibition catalogue, Revisions: Zen for Film, by the same name set out to challenge a number of assumptions about Zen for Film from the perspective of its presentation, archivization, and continuation. From such a multifocal stance, and with potential consequences for analogous artworks, Revisions addresses what is at stake when it comes to the artwork’s presentation—an act shaping not only the (relatively) momentary event of exhibiting objects but also the way in which artworks may be perceived, remembered, and reactivated in the future. Inquiring into the modes of an artwork’s existence, Revisions observes how technological obsolescence and reinterpretation frame the work’s identity. Particularly with respect to recurring installations that undergo the process of de- and re-assemblage, such as Zen for Film, questions regarding its institutionalization, display, and distribution become the ones that affect its existence. In the case of iterant artworks, care for the future, a mission long assigned to conservation, is clearly inseparable from the question of curation; reciprocally, curation cannot avoid challenges posed by questions concerning conservation. Conservation, then, like its “object,” becomes something else—it considers the continuity of artworks on both a conceptual and a material level rather than fostering attachment exclusively to the material trace.

Image 5. Revisions: Zen for Film. Exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York, September 18, 2015–February 21, 2016. Installation detail: Digital interactive kiosk and the book Revisions: Zen for Film (2015). Photograph by Bruce M. White.

Image 6. Revisions: Zen for Film. Exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York, September 18, 2015–February 21, 2016. Installation detail: Main room showing Zen for Film projection and a filmic relic from the MoMA Fluxus Silverman collection.

Photograph by Bruce M. White.

Reconsiderations

The following three “revisions,” nos. 1, 5, and 10, are excerpts from the book-length catalogue that accompanied the exhibition at Bard Graduate Center in September 2015–February 2016. They present several considerations of Zen for Film, each from a different perspective, each posing different questions. I began to delve into the effects of its ongoing struggle with its shape, form, and materiality in the first revision (“Encounters”); the next revision (“How to Exhibit the Work and Its World”) considers the ways in which the work materialized in the exhibition space; and the final revision (“Object—Event—Performance”) analyzes Zen for Film’s ability to become an object, event, and performance. The stance, in what follows, resembles Paik’s posture in a photograph taken by Peter Moore in which Paik’s silhouette—positioned against a backdrop of the white, projected rectangle of Zen for Film—casts a sharp-edged shadow on its surface. The borders of the rectangle are markedly soft and irregular, which, in the era of digital perfection, suggests some distant time, lost in the past—a time when film projectors reified cinematic representation. Aged thirty-three, Paik is turned away from the camera lens, as if he were uninterested in the audience. Deliberately engaging with the theatrical shadow play, an ancient precinematic tradition, Moore—a photographer who dedicated himself to the New York art scene of the 1960s and 1970s—creates an iconic representation of the work by seizing a moment of both Paik’s and his film’s life. We adopt Paik’s contemplative posture: we look at and through the artwork, questioning its material and conceptual status as well as preconceived and established points of view.

Curatorial tasks are often tied to making exhibitions—displaying artworks in a space according to a meaningful concept. The Revisions: Zen for Film exhibition subverted this idea. By presenting the work’s manifestations and explicating its condition, this exhibition questioned what the artwork is and what it has become since it was created, through the course of its many distributions, displays, and manipulations. Zen for Film’s projection, the film remnant from the 1960s, Fluxus editions, and Fluxprograms complicate its existence. The exhibition was not solely concerned purely with exhibiting objects, nor did I aim simply at evoking a minimal aesthetic of display, undoubtedly attractive in other contexts. Indeed, the exhibition strove to unfold the world of an artwork without any potential disruptions, exposing the artwork as artwork—the “thing” and its world, its event, and its process. In the pages that follow, I revisit three perspectives on Zen for Film.

Image 7. Revisions: Zen for Film. Exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery,

New York, September 18, 2015–February 21, 2016. Page from Zen for Film digital interactive.

To access, click here.

Image 8. Revisions: Zen for Film. Exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York, September 18, 2015–February 21, 2016. Installation detail: Main room showing Zen for Film projection and a filmic relic from the MoMA Fluxus Silverman collection.

Photograph by Bruce M. White.

Revision 1: Encounters

—Nam June Paik

No. 1

In a slightly darkened gallery, I am standing in front of a white screen that fills a rectangular wall with a proportional cinematic rectangle. The image appears to blur toward the edges, its contour soft, its corners slightly curved. The film projector clatters relentlessly, transporting a filmstrip through its inner mechanism, pushing its plastic body tooth by tooth through perforations—a rather monotone, yet persistently present, mechanical “soundtrack.” The machine is located on a pedestal slightly below my eye level; I feel the warmth it produces. The shutter interrupts the emitted light during the time the film is advanced to the next frame, unnoticeable but somewhat palpable. The projected image is almost clear and, at first sight, static. I am attending the event, standing inert, without any expectation of an image appearing—I have experienced such an event before. Time elapses. On the screen of my imagination the whiteness delineates Paik’s black silhouette on the white background of this projection, from fifty years ago. In the next take Jean-Luc Godard projects his imaginary pictures on the same blank screen. Thinking about the physiology of viewing the film, I am trying to imagine how—in the perceptual process of my brain and on my retina—the image remains, evoking an illusion of motion rather than an observation of singular frames. Yet nothing happens. I am observing the whiteness. I close my eyes and see a black negative of the projected surface. I am back to vision. People pass by, and in some sense being able to register nonverbal cues, I register their skepticism. Their shadows move away from the projected image unnoticed, effaced. I keep my vision engaged on the whiteness. This contemplation plays out, gradually, when I realize that the whiteness, rather than showing nothing, contains random information—dark traces of different kinds appearing occasionally: smudges, particles, shadows. The eyes, the brain—I think—are somewhat trained to overlook this evidence of film’s materiality. It occurs to me that the longer my observation endures, the more I can see, the more that appears on the initially very hygienic projection. On the abstract bright “canvas” of the image vertical smudges emerge: hairs, blurry grayish stains. In staccato, the image darkens and lightens slightly following the mechanical motion of the projector. I am drawn to its physicality, the sounds of its mechanical processes of display, the sober intensity of nonillusory real time, and the way in which it imposes contemplation and requires engaged spectatorship before it reveals itself.

No. 2

A white cubic space right behind the passage from one part of an exhibition to another is illuminated by a perfectly bright rectangular image. I hardly noticed the entrance while passing through noisy displays and being overrun by various impressions of flickering, visual richness. I enter the room. I stand still. I wait. Nothing happens. Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata enters the space from the neighboring video installation (perhaps Paik’s Global Groove). The image projected in front of me is white, perfectly rectangular, showing regular, sharply cut edges. It seems to just exist, unaffected by anything happening around it or anyone in the room, a white flag of pristine image. Slowly, somewhere from behind, the unobtrusive humming presence of a digital projector becomes recognizable. As I turn away from the image toward the source of the light, I can see the projector located right below the ceiling in the upper center of the wall. I sit down on a chair situated beneath the projector. I sit and wait. My eyes hurt from the whiteness. The word “hospitality” appears in my mind. I sense hospitality in the way I was received in this room, on that chair, but I also register the uncanny impression of being in a place ruled by emptiness and hygienic precaution—a hospital. I can hear lively sounds from behind the walls, a world reserved for somewhere or something else, and I am haunted by an unfulfilled desire to hear and see more, which becomes an unbearable disruption.

No. 3

I bend over to view a round film can in a vitrine at an exhibition. The can is slightly open, concealing a roll of transparent film stock—barely recognizable. For a while I observe it, studying its dimensions and form, the stains of oxidation on the can’s lid and some traces of tape once applied. The film itself is not “clearly” visible. I recall an online image depicting a similar can and three boxes with film leaders, apparently replacements for the loop wound on the reel. It occurs to me, all of a sudden, that there is hardly any difference between this film presented in front of me in a sealed museum vitrine and the virtual version of a photographic image delivered from a server somewhere. Both are distant, both deactivated, both a potentiality rather than an actuality. Still, gazing at the object behind the glass, I attempt to project this film onto the screen of my imagination and guess what it contains. What would it reveal if I were able to view it? I imagine the sound accompanying the projection and myself inspecting the projecting device in a position that would enable me to see the full image and its source at the same time. Yet the film I am looking at is still, somewhat useless, enclosed twofold in the can and in the museum vitrine—a sign of its exceptional value. I am able neither to view it nor to smell it. It is isolated from me and from the surrounding exhibition—still and static, an artifact or relic, one part of an unknown whole, a stagnant remnant of an unfulfilled spectacle.

***

The encounters with Zen for Film open up the question of what the artwork is in relation to the change it has experienced. What happens to the artwork’s identity if we face its presentation and conservation—an experience, an object, a projection, or a relic, or perhaps all of these—simultaneously? They also open up the aspect of changeability that pushes the limits of what can be understood as still the same object, and when it becomes something else. Can a work of art invite change by its very nature? The different methods of exhibiting Zen for Film also raise the question of how curation—as a strategy of presenting the artwork to the viewer that goes hand in hand with conservation—may influence the work’s changeability by the choice of a particular technology. They also question how an artwork functions within a certain historical moment when the availability of technology dictates its aesthetic qualities, and, in the same vein, when this technology changes, following the unstoppable progress of its development.

Describing the three episodes of viewing Zen for Film evokes impressions for me that match three different encounters with this work. The first is with Zen for Film (analogue film loop, film projector), exhibited in the show Bild für Bild—Film und zeitgenössische Kunst at the Museum Ostwall, Dortmunder U, in Dortmund, Germany, December 12, 2010–April 25, 2011. The second, with a digital video projection (8 min., loop), took place at the exhibition Nam June Paik: Video Artist, Performance Artist, Composer and Visionary at Tate Liverpool, England, December 17, 2010–March 13, 2011 place at the exhibition Nam June Paik: Video Artist, Performance Artist, Composer and Visionary at Tate Liverpool, England, December 17, 2010–March 13, 2011). And the third, Zen for Film (canned film reel), occurred at the exhibition The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989 at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, January 30–April 19, 2009.[2] The three forms of Zen for Film could not be more different from one another: the first is a filmic projection; the second, a digital projection; and the third, a film reel. And yet they claim to be Zen for Film —the same work of art. In this revision, I strive to reconstruct the conditions of some of these encounters.

Zen for Film at Museum Ostwall, on loan from the Centre Pompidou in Paris, consisted of a filmstrip (a loop) run through a film projector. Resembling closely the early concept of Zen for Film from the Fluxhall festival, the artwork exposes the process of collecting traces and aspects of a cinematic event as an opportunity for an experience. In the Tate Liverpool variant of Zen for Film, the analogue film projection was replaced by a digital file beamed on the wall in the frozen condition of a hygienic, empty light rectangle. The wall caption revealed that this Zen for Film was a single-channel video, black-and-white, silent, eight minutes long (projected in a loop). A wall label also included the information “courtesy of the Electronic Art Intermix, EAI, New York.” The EAI online database, in fact, holds a digital file of Zen for Film as part of Fluxfilm Anthology: “Zen for Film, Nam June Paik, 1962–64, 8 min, b&w, silent.”[3] Both the EAI and the Tate labels quote Paik’s description of his film as a “clear film, accumulating in time, dust and scratches.”[4] Whereas the EAI description, read in an online catalogue, might serve an informative purpose (we are more inclined to assume that the digital content of a website is different from the analogue character of the film), the Tate Liverpool installation claims a certain status for the film Zen for Film by projecting it as digital video. Apparently a curatorial decision, the digital projection inevitably signifies a mutation of the artist’s initial intention, contained in the choice of a particular materiality of display. Clearly, the projection lacks the materiality of film, which is nowadays symptomatic of a number of exhibitions that include moving images, where DVD projections are substitutes for film (often in the case of Warhol).

It is no less problematic to acknowledge that Zen for Film, as a part of Fluxfilm Anthology, was probably manufactured by Maciunas for inclusion in a package of about forty films. Thus, the artwork’s initial logic was already destabilized by “freezing” it into a single film print. In the Tate variant (and in the digital version of Fluxfilm Anthology, distributed through various platforms) Zen for Film became an artwork with a finite relation to time. The film has been transferred through a digital file with a clear determination of duration—or a partial “documentation” of the work, as it were, a digital palimpsest of one of its screenings. The film leader and the infinite loop projecting itself endlessly have ceased to exist, lending a different element to the conceptual layers of the work. In this instance, Zen for Film lacks both the cinematic character of its analogue medium and the opportunity to experience a particular kind of duration. With its digitization, the process of collecting traces with each projection—as a witness of endless hours of analogue display intrinsic to the initial concept of Zen for Film —has been jettisoned, although the digital display in turn reveals traces other than just scratches, dust, and chance events, in other words, digital forms of decay. Additionally, the transformation into a digital video projection has a further implication: the screening becomes “silent,” a radical reinterpretation of the initially rich sound experience dictated by the clattering mechanics of the projector. Whereas Fluxfilm Anthology includes sound, Paik’s film in this compilation is listed as silent. Either intentionally secured or intrinsic to the given technology, the noise of the apparatus may gain great importance and be considered as preservable in the form of a recording.[5] Clearly, stripping Zen for Film of the audible qualities of its mechanics is a radical move.

The film can for Zen for Film, encasing a blank film leader, is believed to be a remnant of film projections from the 1960s and is a part of the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection at MoMA. Cage recalls that Paik invited the modern dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham (Cage’s partner), to his studio on Canal Street to watch a “one-hour-long imageless film.” [Cage 1991: 22] The film can, then, is a deactivated element of the earlier projection long-since decayed by time. As Jon Hendricks, Fluxus artist and curator of the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, reveals, the Silverman collection holds the only long film version of Zen for Film. According to Hendricks, it was played several times before it was acquired for the Silverman collection. After the acquisition, when the work was loaned for external exhibitions, playing it was not allowed because of its brittle, fragile condition. The work was increasingly presented in a film can while a new film leader (a loop) was played on a film projector. Hendricks legitimizes this by claiming that Zen for Film, being an experience rather than an object, is about the reconstruction of an experience, and that using the old leader, which lies safely in the can, is unnecessary for this reconstruction.[6] Hendricks also recalls a VHS version of Zen for Film and regards its creation as a radical misinterpretation.[7] The video version presents itself as a sort of equivalent of the digital file extracted from Fluxfilm Anthology, despite their being tied to different technologies and media (the first, videotape; the second, film, most probably migrated to video and to an archival digital file—both versions a sort of frozen material of Zen for Film).

Lacking in these encounters, but included in the exhibition, is Zen for Film in the form of a Fluxus edition. These editions include a transparent or white box with—varying by version—one or multiple short strips of film leader. Was the Fluxus edition a replacement for the film run through the projector, or was it an object in its own right? I asked myself this up until October 2012, when I was able to hold the filmstrip in my hands.[8] The yellowed film was obviously too brittle and fragile to be projected.[9] Was it ever projected? What purpose, if any, would be served by projecting it?

So what, where, and how is Zen for Film? The answer to this and other questions can only be sought by looking more closely at the logic behind Zen for Film and by considering its emergence from a range of perspectives.

Revision 5: How to Exhibit a Work and Its World?

When it comes to the moment of exhibiting Zen for Film, the standard line of inquiry may not be sufficient to account for the challenges it poses —and not simply because the general characteristics of an iterant, changeable artwork require that presentation and conservation questions go hand in hand in order to account for its visuality and materiality. In fact, presentation questions never exhaust the technical and philosophical complexities of conservation and preservation work. Although it is accepted practice to obtain permission before Zen for Film can be exhibited, Paik’s work is simply not in fact exhibitable without asking more profound questions about its nature and behavior. In this revision, I will provide some evidence for this claim.

But let us start at the beginning of the process. Among the many ways to display Zen for Film, perhaps the simplest involves obtaining permission to project an empty film leader. Permission could be requested from the Nam June Paik Estate, MoMA, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, or from a number of other museums or collections.[10] Although permission from the Paik estate lacks formal specifications, MoMA includes explicit instructions. When someone wishes to borrow Zen for Film, MoMA stipulates that it is lending only the use of a concept. No physical object changes hands.[11] In the past, MoMA has lent a film canister containing an early version of the film—designated as a relic—to be shown in a nearby vitrine, offering the possibility of displaying two different things—Zen for Film as a projection and a film canister and its contents. Although the canister was often exhibited (as in the Guggenheim exhibition described in revision 1), MoMA’s recent policy discourages presenting the container because it is not now considered integral to the artwork.[12] MoMA also specifies that the borrower is responsible for obtaining a projector and a looped 16mm blank film leader of any length.[13] Finally, the museum prohibits exhibiting the film simultaneously in two locations—a restriction corroborated by the Paik estate—though if Zen for Film is unavailable (presumably because it is on display or on loan elsewhere), the museum has lent Zen for Film from Fluxkit in its place.[14]

The specified display for Zen for Film from Fluxkit requires closer attention, as these instructions differ. Though again, the borrower is charged with procuring the film leader to be used during the installation, MoMA requires further that this leader must measure 8mm instead of 16mm and that the plastic box of the Fluxus edition “must be shown alongside the installation.”[15] The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, however, used a 16mm variant from the Zen for Film Fluxus edition in its own collection to project in its Art Expanded, 1958–1978 exhibition (June 14, 2014–March 1, 2015). The assumption that the film leader from the Fluxus edition is not projectable makes it, in a sense, yet another relic similar to the one enclosed in the canister, although multiplied in a number of existing editions. Another question pertains to the actual difference between the visual appearance of the 16mm and 8mm variants of the film projection itself. Even projectors for films of the same size differ among themselves. If the work cannot be exhibited in two locations simultaneously, while the only criterion of verification is the size of the film leader, how can we define what is different in the produced image without taking the materiality of display into account? How can we educate viewers, and how can viewers know the difference between the projections while contemplating the work? Are the wall label and the presence of a Fluxfilm box enough to create a significant difference? And, last but not least, why does it matter?

According to Jon Huffman, curator of the Paik estate, the coexistence of two film projections in close proximity—for instance, within the geographical terrain of the city of New York—is indeed unacceptable.[16] The dilemma of the sameness of projection coincides with the simultaneity of existence of Zen for Film not only in multiple collections but also within a single one. The MoMA collection holds three boxed editions of Zen for Film. Does prohibiting simultaneous projection of Zen for Film also apply to the projection of the editions, if there are three of them in one collection? Certainly, the nature of an edition is inherently plural, and one can imagine a scenario of a polyphonic symphony of projection, despite the sense of disapproval hovering over the multiple existences of Zen for Film at MoMA. Does traditional museum practice fail to accommodate the complexity of Zen for Film? Is our thinking too deeply rooted in the metaphysics of the static, unique object?

Rather than criticizing individual institutional practices or personal perspectives, my account addresses the paradox of multiplicity so as to point to the complexity of the institutional life of this kind of work. Hypothetically, a projection of MoMA’s 16mm Zen for Film might coincide with a projection of the same variant at the Centre Pompidou, and at the same time a projection of the Walker Art Center’s 16mm Zen for Film from Fluxkit might coincide with a projection from MoMA’s Fluxkit version in New York. But would these variants be exactly the same if nothing changes hands but instructions, formulated or implied? In fact, the prohibition against the simultaneous display of Zen for Film remains largely unenforceable because the Fluxus edition has ended up in many private as well as other institutional collections.

Let us return to the requirement that the film must be looped. Most likely the instruction stems from a later development in the life of the artwork. As we have seen, a looped variant of Zen for Film was produced sometime after the linear projection initially conceived by Paik. Regardless of the genealogy of variants, the implications of the shift from linearity to circularity are ontological. This shift marks the transition from the spectacle of a cinematic event with determined points of beginning and end to an undetermined temporality based on circularity, indeterminacy of spectatorship, and a different mode of accumulating traces. Although including a linear mode of projection in Zen for Film’s repertoire would be reasonable, it would not guarantee an optimal solution, given that the freedom in handling Zen for Film’s concept may result in looping the digitized linear version of Zen for Film from Fluxfilm Anthology.

Yet another aspect of the troubled existence of Zen for Film is the status of the film leader and the canister in which it is contained as relics. An object—often a tangible memorial such as the physical remains of a saint or the saint’s personal effects preserved for purposes of veneration—becomes a relic through a process of authentication, official designation, or both. In fact, there is no certainty that the film canister was ever touched by Paik’s hand, which perhaps explains why the museum now discourages presenting the canister alongside the film projection.[17] Yet when it comes to displaying the 8mm film, the box of the edition must be shown in direct proximity to the projector. Why should the canister containing the 16mm film reel not be granted privileged position next to the work being exhibited, while the Fluxbox is deemed crucial to understanding the work? Although there is no evidence to suggest that Paik ever assigned his authorial seal to these Fluxboxes, perhaps Maciunas did. To be sure, both the Fluxbox and the film canister undoubtedly connect us to the past and signal that the film being shown comes from the container or has a relationship to the box, even though we know that the film being projected is not the same film that sits safely in cold storage or dormant in its case.

Last but not least, looking closer at the logic that lies behind the preservation of the film remnant, should the preservation of all film leaders that have ever run through a projector as Zen for Film be encouraged? Although the museum suggests that all used film leaders should be destroyed, we may nonetheless hypothesize that, if all of them were collected (and I am convinced—given the multiple variants of the film in collections—that some, in fact, have been), this would create an immense archive of physical traces and palpable cinematic temporality ready to be activated in the future.

The entanglement of visuality and materiality in Paik’s Zen for Film raises questions that strain rational thinking about exhibitable objects. As a global, open work, Zen for Film is determined only by instructions, either implied or, at times, produced by museums. What exactly is the function of an instruction? Does it satisfy the economics of circulation, in that it facilitates the reinstantiation of the film in different venues?[18] Does it sufficiently valorize the film as “object”? Indeed, we might go so far as to ask why permission must be granted to display Zen for Film at all. Is the work not a concept, its object-sphere merely an artifactual anchor of its floating identity, a museum prop, or a remnant that secures the work’s value as a collectable commodity? The possibility of multiple spatial and temporal existences of Zen for Film—as in the case of other changeable artworks—goes beyond the established systems of classification and ensures that the conditions for its continuation might not be limited either by institutional or individual authorizations. The major challenge that arises with the moment of archiving, presenting, and conserving Zen for Film is to avoid sacrificing its changeable character.

Revision 10: Event, Performance, Process

This closing revision considers Zen for Film in relation to duration, continuity, and change. Before I delve into this topic, I must first touch on some assumptions that have come to dominate art and conservation theory, particularly in relation to the concept of the object. For a considerable time, both art and conservation theories were oriented toward the unchanging, unique, and authentic object. In restoration, the traditional branch of conservation, artworks were regarded as unique things, often characterized by or defined in a single medium, embodying an intention. Because the goal of traditional conservation was to render “objects” stable, change was a negative force, to be arrested and concealed. This view of change also had an impact on the notion of time. As in William Hogarth’s allegorical print Time Smoking a Picture (ca. 1761), time was associated with the negative aspects of change, such as the yellowing, cracking, and fading of painted layers. With the introduction of changeable artworks in the mid-twentieth century, conservation theories gradually began to shift. New thinking in the field distinguished between the enduring and the ephemeral, which were to be conceptualized and treated as two different conditions of art.

Theoretical discourse had also revolved around the static art object [see Merewether and Potts 2010: 5]. Since the late 1950s, however, artworks gradually became associated with action, performance, happenings, and events. “‘Art’ is an artwork not as long as it endures, but when it happens,” claimed German art theorist and psychologist Friedrich Wolfram Heubach.[19] In a similar vein, American critic Harold Rosenberg turned from the artifactual “thingness” to the act of painting itself. The painting, as an event, results in the physical evidence of a completed set of actions.[20] A painting could be imagined not as an object but as “an arena of activity and performance.” [McClure 2007: 14] Thus, painting would “shed its status as a gerund and, therefore, regain its status as a verb: a thing happening ‘now.’” [Rosenberg 1952: 22] In other words, an artwork “worked.” Fluxus also radically questioned the status of the “art object” both as representation and as a static entity.[21] Art, since Fluxus, was a do-it-yourself enterprise— not a do-it-yourself object, however, but a do-it-yourself reality. The artists associated with Fluxus rejected the functional, sacrosanct art object, the art object as a commodity and as a vehicle of its own history (although this did not prevent Fluxus from commodifying performances later on).[22] Instead, art became something that happens and transforms; an artwork exists in a state of permanent impermanence.

Thinking about artworks can never be divorced from materiality and endurance. As a conservator, I cannot help but wonder what it means that something, an artwork, is impermanent. Or, with reference to conservation, why does it have to be rendered permanent? Where does the division between the permanent and impermanent come from, and how can we conceive of artworks in relation to this dichotomy? The dichotomy probably arises from the problem of understanding artworks as being in time, as having duration, and has something to do with understanding time in terms of endurance within a human dimension in which permanence is measured on a human timescale. A conservator’s or curator’s lifespan, has an impact on conservation and museum practice as well. A masterpiece is thus conceived of as enduring forever and must be conserved so that it does—at least for the “ever” of a human temporal dimension. This is what elicits the idea of a stable, “conservable” object and determines the theories of conservation that I have discussed.

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s distinction between spatial and temporal art [Lessing 1853] and the critique of that division in media and art theories is useful in a consideration of the temporal aspect of artworks.[23] Spatial art has qualities similar to temporal art but might be viewed as “slow” rather than “fast.”[24] This temporal definition allows us to identify a medium’s active and passive response to time and to differentiate among the ways various media undergo change. Artworks such as media installations, performances, and events that actively engage time experience faster change; “slower” artworks, such as painting and sculpture, respond passively to time, which becomes reflected in the aging, degradation, and decay of their physical materials. In its cinematic manifestation, Zen for Film’s constant readiness to shed its physical freight makes it an artwork that actively responds to time. On the artifactual level, the Fluxus editions and relics accept the passage of time, clearly visible in the brittle celluloid and the yellowed labels and plastic casings.

With this in mind, rather than thinking about permanence versus impermanence, let us reconsider artworks in terms of their relative duration, as British performance artist Stuart Brisley suggests: “The issue is not one of the ephemeral versus the permanent. Nothing is forever. It is the question of the relative durations of the impermanent.” [Brisley 2008: 83] Accordingly, one could focus attention not on the problematic permanent/impermanent dichotomy but on the aesthetics and qualities of change, accepting change as a positive value with regard to works of both short and long duration.

Artworks such as events, performances, and processes often require textual stabilization: scores, instructions, scripts, testimonies, and digital narratives; they also generate a vast number of objects and side products that act against their temporal passing. Documentation (film, video, photography, text), props, costumes and leftovers, and relics all fill in for the absence of the event, ensuring that something tangible, legible, and visible remains. The aesthetics of change might be replaced by the aesthetics of disappearance, in which materials are produced and amassed while the original work “disappears.” The work’s transience generates the urge to preserve and collect, which, in turn, expands the accumulating archive. As in Sigmund Freud’s theory of the fetish, this desire to collect physical objects is never stilled. In the context of performance theory, writer and curator Christopher Bedford names this phenomenon “the viral ontology of performance” and relates it to the “long, variegated trace history that begins with the performance, but whose manifestations may extend, theoretically, to infinity” and to the reanimation of performance in a variety of media [Bedford 2012: 78]. In the absence of the event, artworks generate a complex structure of multilayered documentation. Just as the essence of film resides in film stills for Barthes [see Barthes 1970: 41–62], for art theorist Sven Lütticken the essence of true live performance is in photos, films, video, and descriptions [see Lütticken 2005: 24]. Whether the existence of such an essence in film and performance can be claimed, focusing attention on their extended residual history is highly relevant for understanding the nature of their sources.

In a sort of genealogical interdependence—in which facsimiles of documents built on other documents, which in turn were built on other documents, become artworks themselves[25]—such “stratigraphy” of documentation may never cease to expand, continually depositing new layers on the already accumulated sediment. New interpretations, technologies, cultures of actualization (permitting certain things while restricting others), and multiple locations in which the work exists or is reinterpreted render the achievement of the totality of an artwork’s archive an illusion. Subsequent interpretations will thus rely on fragmented information and will never be unbiased or complete.

From a temporal perspective, Zen for Film might thus be conceived of as a performance of sorts, in which the action is enacted by the projector and witnessed by the audience. The mechanical embodiment consists of an apparatus that projects a blank film on a vertical surface. What remains of this performance is a film loop endowed with traces, a temporal marker and reference to the many hours of labor, an individual object to be appreciated as evidence of the works performance. Dependent on the variant of the projection and contingent on value judgments regarding what might be permitted to enter the archive (whether the object is deemed valuable, historical, or worthless), the residue of this performance—the used film—is “conservable” and might be preserved. Potentially, it might—just like the earliest film and the boxed Fluxfilm editions—become a vestige of times long past, a fossilized filmic artifact/relic cherished for its link to the past but also precisely for this reason condemned never to see the light of the projector again.

Could this be the reason for the museum’s directive that filmstrips used during the course of any reinstallation be destroyed? One may speculate that too many remnants would diminish the value of the relic owned by the museum. The value of the relic rests not only in the singularity of a historical event but also in the commodity value that it acquires over time as a nonreplicable, unique, and fetishized collectible. MoMA’s stipulations may then limit the realization of Zen for Film as Paik conceived it, as an infinitely repeatable event. Rather than being final products, according to Dick Higgins’s theory of the “exemplativist” nature of an artwork, the objects resulting from the realization of such a work’s concept (but also from its notation or a model) are only examples [Higgins 1978: 156][26] The practice of imposing limitations on Zen for Film’s open character (which pertains not only to the openness of the initial concept but also to Fluxus’s open-ended, mass-produced editions) might be understood as an intervention in the symbolic economy of artworks. This practice fosters a consumption of commodified products and undermines the open, active, and social process involved in the contingencies and instabilities of Zen for Film’s performance.[27]

“Love objects, respect objects,” pleads American artist Claes Oldenburg, referring to the creative act of selecting and caring for what remains after a performance. He continues: “Residual objects are created in the course of making the performance and during repeated performances. The performance is the main thing, but when it’s over there are a number of subordinate pieces, which might be isolated souvenirs, or residual objects.” [Oldenburg 1995: 143] These “acted” or “domesticated” objects bear memory and a history that might unfold in the future [see Brignone 2009: 67]. They also fulfill the desire to stabilize and preserve objects in accordance with traditional (Western) museological standards. If works are not meant to function as collectable objects but become such (as has Zen for Film’s filmic relic), the process of commodification dictated by market economies reinforces conservation and “conservationist” gestures as exemplified in “keeping” the material of the artwork rather than continuing its concept, tradition, or ritual of making. The process of musealization[28] counters disappearance. The wish to cure grief and nostalgia with an object, a fetish, is deeply rooted.

Thinking about the temporal relativity of artworks can have fascinating consequences. If one inverts the standard assumption that an artwork is an object, a question arises as to whether all artworks might be conceived of as temporal entities—either long or short events, performances, or processes. Accordingly, traditional paintings or sculptures would become artworks of long duration. This might also invert conventional thinking in conservation and in curatorial and museum practice. Not only would the ephemeral/permanent dichotomy be revoked but also the problem of grappling with the nature of the “new” (multimedia, performance, event) through the lens of deeply rooted ideas about the old stable object. Indeed, as one more consequence of inverting standard assumptions, traditional artworks could now be approached through the lens of the “new.” Seen from a conservation perspective, this inversion seems to be a novelty that requires some attention, although I cannot pursue it here.

Performances or events have a compressed temporal presence but are no less material. Further, the amount of material produced by an artwork might be seen as inversely proportional to its endurance in time. In the process of musealization and commodification—and in response to the urge to secure tangible things, leftovers, props, relics, video, and film—documentation may even acquire the status of the artwork itself.[29] These things, of course, might be kept “forever,” satisfying the traditional materialist attitude. This is not to say that long-duration artworks fail to produce documentation—quite the contrary. Nevertheless, the documentation of long-duration works cannot match the mass of documentation and residual objects produced by performance. Compared to long duration objects, short-duration works are more varied and richer in genre and quantity and in their potential to become artworks. But what would be an analogue of the performance’s relics and leftovers for traditional objects? Perhaps the “stable object” is its own relic and remnant, accumulating the strata of its own making and all past interventions (cleaning, retouching, etc.). Although works by acclaimed artists would be valued as relics, the unsigned painting bought at a thrift shop for five dollars might be conceived of as the leftover of an unappreciated performance.

***

Conceiving of Zen for Film as performance recalls the aesthetic theories of philosopher David Davies [Davies 2003]. Drawing on Charles Sanders Peirce’s semantic distinction between “type” and “token” [Peirce 1906], Davies argues that artworks should be regarded as “action tokens” rather than “action types.” Generally speaking, this much-debated distinction applies to multiple arts, such as music and photography, in which a performance of a musical work or a print of a photograph are tokens exemplifying a universal type. But not all philosophers agreed with this distinction. Building on Gregory Currie’s suspension of the distinction between singular and multiple arts (of which Goodman’s theory of symbols is an example), Davies offers a twist on this suspension by claiming that all artworks are token events rather than type events.[30] Coinciding with the temporal turn in the arts of the 1960s and its theoretical underpinnings (discussed at the beginning of this revision), Davies’s model views the real work as the process, the series of actions by which the artist arrives at his or her product—not the product itself. According to Davies, the painted canvas is a “focus of appreciation” through which we regard the artist’s achievement and which embodies the artist’s idea and work. The kind of focus determines the physical object; some foci require the analysis of the enactment.[31]

Although it is interesting to identify an artwork in terms of the sort of creative action an artist has undertaken, this approach, if viewed from a reverse perspective, might be pushed further. If one pays careful attention to the modes of an artwork’s creation, to how it came into being, the conditions identifying artworks might equally be provided by observing their “afterlives.” An artwork’s afterlife concerns the time after the work “happened” (in Heubach’s sense). This afterlife is important in identifying what and how the artwork is, which is, in fact, the only reality to which we have access. The process of creation does not provide the sole source of information about what an artwork is. Thus, instead of identifying—or rather imagining—the past retroactively, the proposed approach insists on looking at the present. Other options include reenactment, expanded trace history, actualization, and also attention to transition—decay, disintegration, and degradation.

My proposal falls within the realm of “type” theory, but unlike the theory of art as performance, it focuses on what is left—the object, leftovers, props, residues, documentation, and so on.[32] Thus, although both theories concern the question of when the artwork is, my approach focuses on a mode of studying artworks that shifts from how and when art was created, to what is left from the creative act, what has become of it in the present—the only reality and point of access to the work. Consequently, the shift from product art (traditional artworks) to process art (artworks after the temporal turn among artists in the 1960s and in art critical theory) entails a concern with that which remains.[33] It follows then that artworks might be identified in relation to their temporal characteristics, so that they are understood as durational, yet distinct. In performance, the defining parameters are duration and intensity.[34] Although subject to the relativity of judgment, these qualities make it possible to distinguish, depending on context, among event, performance, process, and object and to overcome the opposition between the permanent and the impermanent artwork. In fact, Zen for Film presents us with an entire range of temporal durations. Although, as I have stressed, the distinctions among the categories of event, performance, process, and object are relative, if Paik’s film is conceptualized within a particular context, it might be grasped as an event (a nonrepeatable cinematic event), a performance (a performed spectacle, dependent on the length of the viewer’s engagement), a process (accumulating traces while it is projected), and an object (an apparatus, filmic props, Fluxfilms, and filmic remnant/relic).

The strategies of event-based artworks such as Zen for Film reflect the ways in which the works are conceived. Countering the historical ban on reproduction [Phelan 1993: 3], performance may be reenacted, process redone. Despite the singularity and irreducibility of the experiential qualities of an event, one must recognize that the event will be repeated, even if differently.[35] According to Deleuze, recurring iterations always involve deferral and difference.[36] And yet the “technique” of repetition does not apply to artworks as physical objects. Because it is not compliant with prevailing museological and conservation culture, such a redoing of an object will always be classified as a copy or, in more derogatory terms, a forgery, depending on valency, rules, and legislation. And yet, do performance, event, and process not result in “objects/originals”?

The notion of forgery recalls Goodman’s distinction between forgeable/ autographic and unforgeable/allographic art. Generally, allographic art may be characterized by short duration; autographic, by long duration. To stress the temporal dimension of my argument and draw attention to another of its aspects, I would like to replace allographicity and autographicity with Michael Century’s neologisms “allochronicity” and “autochronicity.” Century employs these terms in relation to the specificity of scores.[37] To apply Century’s terms to the temporal relativity of artworks, “allochronic” would refer to artworks that are not tethered to a specific temporality and that are reperformable, while “autochronic” would designate artworks that have a specific, fixed relation to time. Autochronic artworks are those previously treated as long-duration, quasi-stable objects; allochronic artworks may reoccur in repeated iterations.

Zen for Film’s relic would thus assume the character of an autochronic entity, while Zen for Film projections would be allochronic. Again, this distinction is only viable in the context of traditional Western museological (and conservation) culture, in which the replication of the long-duration artwork is not accepted as a valid strategy for its continuation. Staying close in its relationship to “token” theory by denying the division between multiple and singular artworks, the concepts of autochronicity and allochronicity assure an artwork’s location in a time structure and its identity as a temporal entity.

***

In sum, the turn taken by artworks created in the post-Cagean era, such as Zen for Film, not only reflects a general change in the concept of art, of what art can be, but also elicits a shift in thinking about its presentation and continuity. If we consider the order of things in conservation and curation seriously, apart from its theoretical implications, the suspension of the distinction between traditional “enduring” objects and “ephemeral” short-duration objects would release us from the antinomies of everyday museological practice. Instead of asking conservators to perform the impossible feat of arresting change, we could think of artworks of all kinds as ever-changing and evolving entities that continually undergo physical alterations and transitions. Accordingly, curation and conservation might be grasped as temporal interventions in artworks. Rather than assigning regenerative capabilities to conservation (through which the artwork is sometimes wondrously returned to its “original state”), the conservator would instigate just another change in the work in its long- or short-duration existence, compliant with archival and cultural permissions and/or limitations. As I have suggested, an artwork’s own archive, dependent on the cultures of conservation, establishes rules and sets limits on what can be said or made, with reference to the present as well as the past. Although performance theories may not be the only way to continue this inquiry, I believe that they offer an opportunity to rethink traditional objects in terms of duration. This, in turn, can expose the hidden deficiencies of long applied theories and free us once and for all from a blind faith in the permanence of objects that has for too long prevented us from understanding the inherent reality of change.

Afterword: Assembling the Work

The Revisions exhibition fully demonstrated how, through the making and remaking of Zen for Film, its single manifestation gave way to a fruitful multiplicity. In the course of its many realizations, sanctioned by the institutional stakeholders and stewards of the Paik estate, the work confirmed its quality as radically changing, self-differing.[38] My work related to the loan acquisitions with MoMA and the estate taught me not only how Zen for Film moved through time, changing appearances, forms, and modalities of its physical display apparatus but also how the current institutional politics and knowledge of actors involved in making decisions, whether at the museum or at the estate, impact of the conditions of the work’s identity. In fact, the Zen for Film exhibition, assembled from pieces scattered throughout institutions and displays, was in constant operation of its own identity formation—one that is never complete or finished once and for all but rather is open to an infinite number of material actualizations.

The actualizations of the work are contingent on the archive—an aspect addressed throughout revision 10 and to which I will return within these pages. The virtual sphere of the archive—the knowledge about the work, the recollection of its different states and realizations, the verbal instruction and permissions—complements the physical archive extant in written or photographic documentation, archival remnants and artifacts, projectors, filmstrips and hardware. The actualization of the work, a transfer from its virtual to its physical state, is possible only on the basis of such archive. But the movement here is not one-directional: An actualized work enters the archive and becomes a basis for its future actualizations. There is an infinite potential to such movement, and only forgetting or the destruction of the material and documentary traces might annihilate the work. The way in which the work is actualized is contingent on cultural permissions, situated knowledge and the political, economic and social factors that allow certain things to come into being and restrict others.[39] It might also be claimed that the work is contingent on what Michel Foucault calls an “apparatus,” a “heterogeneous ensemble of discourses, institutions, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions—in short, the said as much as the unsaid. […] I understand by the term ‘apparatus’ a sort of […] formation which has as its major function at a given historical moment that of responding to an urgent need. The apparatus thus has a dominant strategic function.” [Foucault 1980: 194] [40]

Independent of its archival reliance, the narrative constructed around Zen for Film’s existence might be supported by the notion of an assemblage, a conglomeration of elements, human and nonhuman, consisting of active physical artifacts and actualized performances. An assemblage, according to political theorist and philosopher Jane Bennett, is a swarm of material agencies. The world does not consist of raw, inert and passive matter juxtaposed by vibrant life. Instead, Bennett claims that things have the capacity “not only to impede or block the will and designs of humans but also to act as quasi agents or forces with trajectories, propensities, or tendencies of their own.” [Bennett 2010: viii][41] Following Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s material vitalism [Bennett 2010: viii],[42] Bennett believes in active materiality that assembles and unfolds agency between things. “Assemblages are living, throbbing confederations,” according to Bennett, “that are able to function despite the persistent presence of energies that confound them from within. They have uneven topographies, because some of the points at which the various affects and bodies cross paths are more heavily trafficked than others. […] Each member of the assemblage has a certain vital force, but there is also an effectivity proper to the grouping as such: an agency of the assemblage.” [Bennett 2010: 24] Assemblages are sums, they cannot be totaled; they exist only in particular times and places and are not governed by any central force.

Perhaps, then, the concept of assemblages as a working set of vibrant materialities and interactions of bodies and forces might be helpful in approaching the multiple worlds of Zen for Film.[43] As we have seen, the acted-upon-work becomes many material, performative, and performed things, but it also, in its ongoing life, acts upon and exerts agency on the participants.

Things can do things. Placing the work and humans, the nonsubject and subject, as equivalently empowered actants, we might recognize that these things—the artworks—have the ability to produce effects, to make something happen. Instigated by the request for exhibitions, the museum curators and specialists formulate and revise protocols, shifting between the imperative of physical preservation and the conceptual pragmatics of the work. They enact the boundaries of the work and test its conditions of possibility. The work’s agency has also underpinned both the present and original writing, throwing me into the struggle with many accounts and (often conflicting) personal and institutional narratives. Last but not least, issuing active power, the work also acts upon the viewer and receiver, who perpetually questions what is being seen and what has, of necessity, been overseen.